Completing a GT40

As Told by Eric Dean

Photos by Steve Temple and Eric Dean

Like probably most guys reading this magazine, I’ve been obsessed with cars since I was a boy, but it really started spiraling out of control as a twenty-something pining over a Porsche 911. That’s when I bought the only one I could afford and systematically replaced most everything on the car. Before I knew it, I had three times its value into in my “Economical 911”.

My next mistake was to start doing track days. I soon realized nothing made me happier than flogging a car around a track. And so, it was time for an “Economical Racecar.” There is no such thing. Nevertheless, enter my vintage Formula Vee, followed quickly by Formula Ford. And so on, and so on. Apparently, learning nothing from my 911 experience, I bought all as project cars. After restoring three vintage formula cars from the ground up, I felt I was ready for my next project.

I always dreamed of one day building a GT40— perhaps when I retired—but not anytime soon. In the spring of 2013, I found myself moving from Detroit to San Francisco and couldn’t stop thinking about GT40s. I found myself watching old LeMans footage, collecting more GT40 books, and reading articles. My obsession fully set in. I daydreamed of tearing up the rugged California coastline, or around Sonoma Raceway or Laguna Seca—suddenly retirement seemed like a long way away.

Then, in the Fall of 2013, I flew back to Detroit for a friend’s wedding and decided to drive my “Economical 911” four hours north to the ceremony. Before setting off, I stopped in to check out RCR—which, serendipitously, was only a half a mile away from where my car was being stored. That’s when I met Fran Hall and witnessed firsthand how beautiful these cars were.

The craftsmanship of the all aluminum monocoque is exquisite. The welds are beautiful and the machined suspension components are a work of art. Fran and I chatted about how this was a hands-on project that requires the builder to do more than most kits on the market.

“Perfect,” I thought, “I love a project.” 20 minutes later I was signing paperwork. Six months later I’d have my very own GT40 assembled and be thrashing it around Northern California—or so I imagined.

Several factors made this expectation impossible. There were times when I found I was missing parts, had the incorrect part, or needed to modify the existing ones. In addition, my experience building and restoring race cars didn’t prepare me quite as well as I thought it would. I soon realized that all cars I previously built, at one time, had been whole. Not this one. Moreover, the Formula cars that I built were much simpler, easier to work on, and didn’t have the systems required on a street-legal vehicle.

Building an RCR requires significant automotive expertise, and I imagine it helps if you have an engineering degree, which oddly enough, wasn’t available at the art school I attended. As reality set in, I decided that my new goal would be to finish the GT40 by the time I was 40 in January of 2015.

I make a point of finishing projects, and I rarely back down from a challenge. Admittedly, I nearly did with this one, on at least one occasion. In fact, at one point, I threatened to put it up on eBay for someone else to finish. Building an RCR GT40 simply isn’t for the faint of heart. What you save in money you pay for with blood, sweat and tears—but when you do finish—it is truly your car, and that makes it all worth it.

There are two things that kept the project on track: I built the car at my friend Geoff Gates’s hot rod shop, Alloy Motors, that is outfitted with lifts, a full machine shop, metal shaping tools, welders, a paint booth, and extra help when needed. And, perhaps the smartest thing I did, was hire my friend Dave Lyman, affectionately know around the shop as “Super Dave”, who is an amazingly talented engineer, designer and fabricator to work along side me on evenings and weekends. That decision alone probably shaved a year off the project.

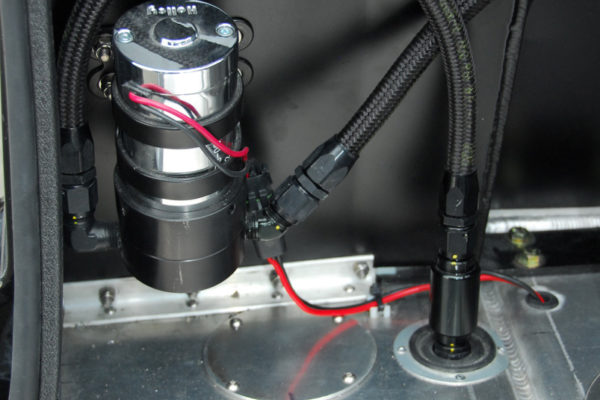

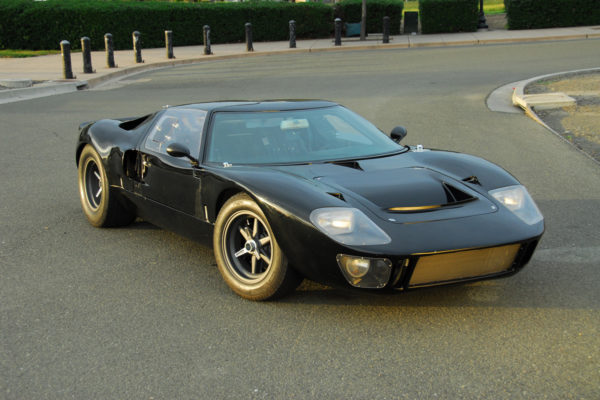

My vision for the car was to keep it as stripped down, lightweight and raw as possible. No interior carpet or modern amenities. A purposeful race car that can go fast, handle and still be driven on the street. I decided to go with a Keith Craft 331ci small-block Ford mated to a Porsche G50 trans. The engine puts out 440 hp, 425 lb/ft of torque at the wheel, and the fully assembled car weighs in under 2400 pounds. That should do it.

I realized early on that you need two people for much of the build. The body goes on and off a hundred times before the car is done. And because so many things work in concert, it pays to fully reassemble the car at every major stage of the project to ensure everything fits.

For example, I made the mistake of fitting the dash, elegantly cutting it out around the roll bar, sanding, filling and painting with the doors off of the car. When I put the doors back on the passenger side wouldn’t close due to interference with the dash.

Another example of this problem is body fitment. The center body section (the spider) determines where your dash sits and where the front and rear clip land relative to the wheel well. So, you need to consider seemingly unrelated things like wheelbase, steering wheel position, firewall position and door gaps all at the same time for everything to work. One of the more frustrating moments was when I installed the firewall, and the body no longer fit, because it forced the spider too far forward. This was one of those times where I had to walk away for a while and come back to the car to see the solution. As it turns out, I just had to put the firewall in the sheet metal brake, and put a 5 degree bend in each side to put everything where it needed to be.

The point is, that you can’t expect everything to be perfect right out of the box. The fabrication is top notch from RCR—but as with any low-production vehicle that is handmade—it requires a lot of additional work to make things perfect. I experienced this simple fact countless times.

Lastly, if you’re going to build an RCR GT40, there are many references online from other RCR owners that have painstakingly documented nearly everything. This is extraordinarily helpful—as much for what to do, as it is for what not to do. It can get overwhelming though. I found that I could get lost down a rabbit hole for hours researching how I might design the door latch mechanisms, mount the headlights or get the body to better align. Since my day job doesn’t really afford me a lot of free time, I soon realized my time was often better spent just diving in and figure things out rather than scrolling through forums. You have to know when to stop reading and start wrenching, or the project could seemingly go on forever.

All the challenges aside, two weeks prior to my 40th birthday I drove the GT on the street for the first time. It was one of my proudest moments. On the day I turned 40, my incredibly thoughtful girlfriend (who as a result of this project has seen a lot less of me than she’d like over the past two years) did something I never could have expected: she and a few of my closest friends organized a personal track day—all to myself—at Thunderhill Raceway to enjoy the GT40 at speed. I’m a very lucky man.

To this day, I’m still dialing the car in on the twisty roads in the Oakland Hills, before it all comes apart again one last time to be painted, but I can already tell it exceeds my expectations.

It’s terrifyingly fast, mind-numbingly loud and completely uncivilized.

It’s perfect really.

Comments for: 40 X 40

comments powered by Disqus