Jason Pall built a copper colored street rod from parts

Text and photos by Steve Temple

Spare change seems to accumulate from nowhere. Suddenly you’ve got a pile of coins on your nightstand, gathering dust. Or they end up in a jar that becomes a hefty paperweight. And pennies are the worst, worth more in metal than currency, but you don’t want to throw them away, either.

All of this makes us wonder about Jason Pall’s “Bad Penny,” a copper-coated amalgam of Ford and Dodge components that just keeps turning up, no matter what. According to Pall, the ’23 Dodge body with ’26 Ford rear quarters was first built back in the Sixties, with lots of stick and gas welding on it, all pretty rough. No dash, floors, firewall, deck lid or filler panels, with the rockers rusted out and wheel wells cut out. There it sat, just getting dusty, yet not quite ready for the trash heap.

Yet even after a couple neglectful owners, this Bad Penny kept coming back. Pall plucked it off Craig’s List for the measly sum of $250 in 2007. Fortunately for Bad Penny, he’s not reluctant to rub a few old coins together, having all sorts of rides at his shop Bear Metal Kustoms.

Pall’s particular approach to building cars can’t be dismissed as merely glorified rat rods. “I kinda stay away from rat rods,” he says. “I refer to it as traditional style. I just like things to look mechanical. I don’t like to hide it, I want it in your face.”

That rugged individualism seems to work well. Previously he also built a ’23 T-bucket dubbed “Pretty Penny.” So why bother its evil twin, a bent pile of Blue Oval and Mopar parts?

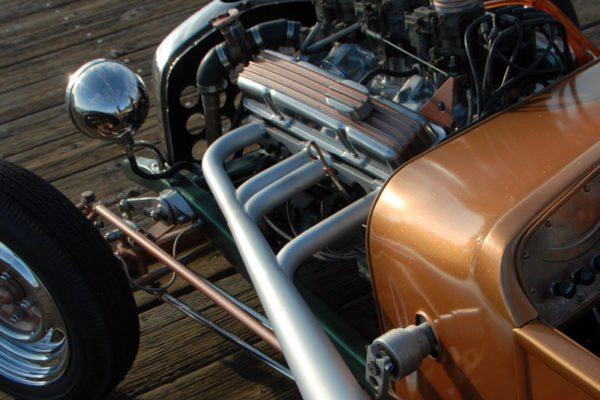

Well, like that proverbial bad penny, it just wouldn’t go away. And so he figured out how to put it to good use, to showcase his shop’s metalworking skills. He began by fabbing a chassis out of some old Ford frame rails and lots of tubing. He then added a cross leaf up front, quarter elliptical springs and a three bar rear end, along with friction shocks from Speedway Motors. A few months later, after dropping in a 350 Chevy with a Tri-power 3x2 intake, it was a driver. But the body was still rough.

“We had it running as a ratty little roadster for a while,” Pall recalls (despite his avoidance of rat rods). But then he came to the realization that there actually might be some precious metal underneath all those layers of tarnish, so he and immediately set to work, polishing this old penny even harder, redoing it completely.

After pulling the car apart, cleaning the chassis and reworking a few things, Pall replaced all the bad parts with custom tubular cross members, motor mounts, trans mounts, suspension. Instead of an abrupt Z-cut to lower the ride, the frame has a 3.5-inch sweep forward of the firewall. This smoother transition took a lot more effort, requiring about 50 partial wedge-shaped cuts, so the frame could be bent and then re-welded.

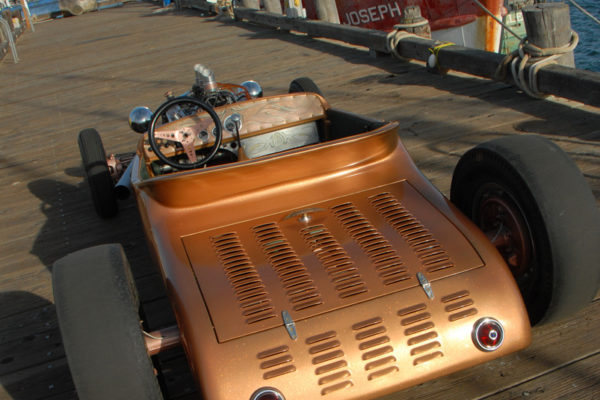

The radiator, electric fan and electric water pump are all mounted under louvered deck lid. To give this rod a competition quality, he threw in a Sprint car steering box with a control rod running along the drivers’s side of the body, and a quick-release steering wheel. The brake pedal and gas pedal swing off steering box mount. The stoppers are Chevy discs in the front, and ’56 drums in the rear, putting the bite on original vintage ‘60s Radir tri-rib rims. The front tires are Firestone 5.0x15, and Hurst slicks in the rear, measuring 235/75R15, were made by Adam’s Hot Rod Rubber.

The bodywork is when Pall really had to dig into his pockets for some spare change. Where the body parts were simply scabbed on before, he flowed the transitions from the 1926 Ford roadster quarters into the 1923 Dodge body, and widened the cowl by 2.5 inches. The deck lid, lower and upper filler panels were all handmade, punched with louvers.

“That was a bear of a job,” he quips, punning his company name. On top of the cowl is a flip-top gas filler from an abandoned Morro Bay boat, secured with slot-head brass machine screws to a square plate. “I’m cheap when it comes to my own stuff,” he laughs.

The dashboard was missing when the body was purchased, so he built a custom piece and covered it with copper sheeting, matching the gas-filler plate. Ditto for the exposed bolt heads on the transmission tunnel.

The overall intent is deliberately rough and mechanical, a mix of neo post-industrialism, along with a dash of art nouveau—the only decorative aspect on the dash is some pin striping, painted by Doug Dorr.

In keeping with the bare-metal theme, and to give the nose a distinctive look, the Ford stainless model A radiator cowl was sectioned and then fitted with a custom copper insert peppered with made with 20 large dimple dies. The effect is dramatic, using a simple technique of metalwork to make a bold, artistic statement. This Bad Penny really jingles when it rolls.

A set of Speedway Motors stainless headlights frames the custom chrome cowl, and Olds taillights bring up the rear. Jimmy Z dressed the cockpit with a antique-green upholstery that complements the copper color of the body—finished with several layers of Dupont Chromabase copper, Roth copper and orange flake.

While the engine is fairly stock, except for the custom carb scoops from James Maund Speed Equipment, and the Lake-style headers, the car is so light, it doesn’t need much extra power running through the Turbo 350 tranny to produce some prodigious performance. One time a late-model Corvette began tailing him at high speed, and when the driver eventually pulled up next to him, he exclaimed, “You’re nuts, driving car that low at over a hundred, and with no windshield or seat belts!”

Well, to coin an old phrase, this Bad Penny turns on a dime and gives back change.

Comments for: BAD PENNY

comments powered by Disqus