A pair of contrasting Corvette Grand Sport replicas

Story and Photos by Steve Temple

Is it live or is it Memorex? That was the tag line back in the 1970s for a commercial touting the reproduction quality of audio cassette tapes. But this phrase might also be applied to these two Corvette Grand Sport replicas, owned by Udo Noger, since they are very close copies. Yet they also improve on the original in some significant ways, as we’ll see. More about those items shortly, but first some background on the Grand Sport and its legendary designer, Zora Arkus-Duntov.

Out of all the Corvettes ever built, the 1963 Grand Sport racer still commands a singular level of respect. It was one of the few cars of its era that bested Carroll Shelby’s vaunted Cobra — albeit briefly before General Motors yanked them off the track. Only five Grand Sports were ever built, and they are considered the most valuable and coveted Corvettes ever.

Throughout his Corvette career, Zora fought with GM management over the role racing played in shaping the direction of the production car. In an era in which corporate-sponsored competition was officially banned, he was legendary for putting together secret prototypes and dealer-sold, “backdoor” racing packages. That should come as no surprise, considering his exploits on the road courses of Europe.

When Zora attended the 1953 Motorama at New York City’s Waldorf Astoria hotel, he was both enamored and disappointed by the debut of the Corvette roadster. He was struck by the potential of its lithe lines, yet clearly underwhelmed by the tepid power of the Blue Flame Six engine.

A famous letter to Ed Cole, Chevrolet chief engineer, about suggested improvements followed, and so did his employment at GM in May 1953. Fortunately, Chevy execs listened, and Zora was credited with saving the Corvette from a premature demise since sales in the first two years of production were pitiful. Some have called him the “Father of the Corvette,” but technically that designation should go to Ed. Instead, Zora was the one who gave the Corvette an injection of testosterone.

Never one to hold back, Zora knew that only by stuffing the then-new Chevrolet 265 ci V8 into the engine bay could the Corvette be taken seriously. He wasn’t content as a desk-bound, slide-rule engineer though, and he was willing to man the steering wheel on the track in order to prove his point.

“To establish the sports car, you have to race it,” is one of his more famous quotes, a dictum that he followed his entire life. He spurred development of many performance components, along with the record-setting Super Sport and the CERV (Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicle) cars.

Lessons learned from the CERV 1 were applied to one of his most significant contributions to Corvette production cars: the ’63 Corvette. Its independent suspension was far lighter and more advanced than that of the solid-axle C1 Corvettes.

But Zora had bigger things in mind for the then-new Sting Ray: the Grand Sport program. Despite friction with upper management, he obtained some unofficial assistance from Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen, Chevrolet’s general manager, who provided a black-ops budget and a secret skunkworks.

Back then, a factory Corvette weighed about 1,000 pounds more than the Cobras that were beating it, so Zora put the car on an extreme diet in order to make it competitive. Fitted with a tubular space frame, thinner fiberglass body panels, and an aluminum small-block Chevy, each of these Cobra-skinners weighed about 1,800 pounds or so and boasted as much as 550 horses. Known simply as “The Lightweights,” Grand Sports were created to win FIA endurance races, including the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

How do the two Grand Sport replicas shown here measure up to the original? Starting with the coupe, it was built by D&D Corvette back in 1989. Udo purchased it from Doug MacDonald, brother of famed Corvette and Cobra race driver Dave MacDonald (hence the tribute message on the window glass). The car was stored in the desert, between Blythe, California, and Lake Havasu City, Arizona. Understandably cautious about carrying a briefcase stuffed with cash out in the middle of nowhere, Udo brought along an armed bodyguard as extra insurance. The deal went down without a hitch, though, and he drives the car regularly (along with his two Cobras and an array of other performance machines).

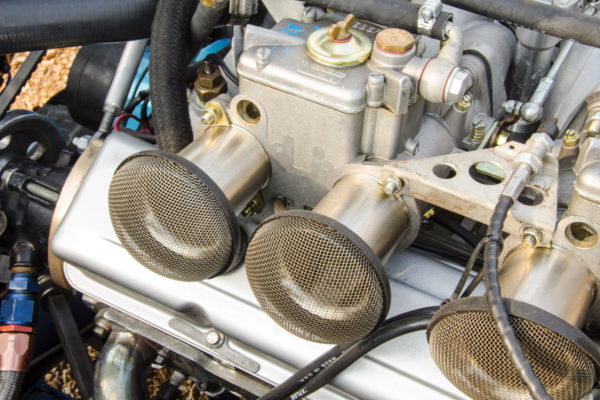

This replica’s custom tubular chassis employs Corvette C4 suspension, an improvement over the original’s setup, with Aldan coilover shocks and Wilwood disc brakes. The engine also ups the ante on the original’s 377 ci power plant, which delivered outputs ranging from 485 to 550 hp. The Weber-equipped ’71 Chevrolet V8 in Udo’s coupe displaces 406 cubes and pumps out 600 horses. A T56 transmission actuated by a Centerforce clutch transfers power to the C4 rear end.

He relishes driving the car just about every week, kicking it through the mountains of Southern California. Realizing that it’s built for racing, Udo says, “You really have to watch what you’re doing with both cars. They’re extremely powerful.”

As for the roadster, he had been looking for one all over the country for several years and by chance came across the car at a stoplight on his way to a nearby car show. Even though it wasn’t for sale, Udo made the owner an offer he couldn’t refuse. (And no armed bodyguard was needed to close the deal either.)

Built by Jeff Leach of Mid-America Industries in 2000, this Grand Sport replica is based on a factory Corvette chassis updated with Aldan coilover shocks and Wilwood disc brakes. The engine is modernized as well, a Chevy 502 big-block cranking out 620 hp. Udo points out that it feels a bit heavier up front, but it’s not significantly different. “Both cars are tough to drive,” he admits. “There’s no driving comfort. My Cobras handle better.” But that’s what he likes about the Grand Sports, the challenge of manning the wheel.

These traits are partly due to their significant upgrade in power, which is a good thing since they don’t have the same weight reduction that the original Grand Sports needed to win on the track. Yet this extra poundage is not necessarily a drawback. The original lightweights were unstable, temperamental beasts, and piloting them was not an exact science.

In contrast, these replicas are far more tractable than the authentic track car. While they have the original’s racy body shape — bristling with a front air dam, hood extractor, fender flares, and cooling scoops — the cars feel far more substantial. They don’t oversteer and understeer at the same time, as the authentic car was prone to do. And the doors shut with a solid thunk, rather than a rattle. Noise attenuation is somewhat better as well, though the exhaust note is still intimidating.

Ultimately, these two Vettes are far more than just grand illusions. Their exteriors show all the bark of the original. But with updated engines and suspensions, these Grand Sports surely have a bite all their own.

Comments for: Grand Illusions

comments powered by Disqus