Reflecting on the 15-year buildup of an FFR Daytona Coupe

As told by Russ Foster

Photos by Steve Temple

After becoming interested in racing cars in 1949 at the age of 11 from reading auto magazines, I became an avid spectator at many of the iconic SoCal race circuits from the mid ’50s to the early ’60s. These included Torrey Pines, Paramount Ranch, Santa Barbara and Riverside where, in 1957, I witnessed the debut of Dan Gurney onto the world stage against a star-studded field. I was hooked!

Even so, I was on active duty in the U.S. Navy from June 1962 through December 1966, so I missed virtually the entire golden era of the Shelby Cobra. It was not until 1995 at Sears Point Raceway that my wife and I stumbled upon the reunion of the Shelby team celebrating the 30th anniversary of the World Manufacturers’ Championship in ’65. Gathered there were four of the six original 289 Daytona Coupes. I took note of that, thinking, “Those things look very good — and they sure have huge back windows.”

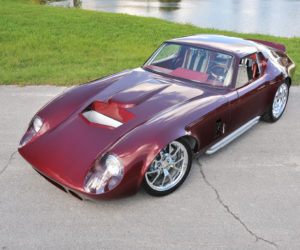

That vivid memory persisted for many years. Then, in late 2000, I came across a one-page article on Factory Five Racing’s intent to offer a Daytona Coupe kit. Up until this time, building a replica of a bona fide race car had been a distant thought. I have always been a coupe fan, but no kits had inspired me. Here was an opportunity to build a replica using the same type of engine that the originals had. Subsequently, I placed an order. The kit, FFR coupe #17, was delivered in June 2001, and the adventure began.

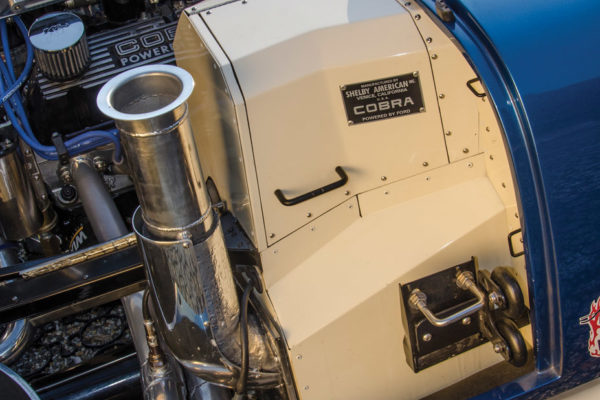

I decided to pattern my build after serial number CSX2299 as it appeared in the 1965 12 Hours of Sebring. That’s because 2299 was one of six Ford 289-powered Daytona Coupes that played a major role in winning the World Manufacturers’ Championship for Shelby American in 1965.

The exterior of my car is a reasonable facsimile of the original, with period-correct 1965 Ford Guardsman Blue and Wimbledon White paint. The wheels are 15-inch Halibrand-style FIA pin drives with Wimbledon White center sections and polished outer rims. Windshield slats divert airflow to the rear brake air inlets behind each door. In keeping with the original’s competition livery, the exterior is adorned with large racing numbers and numerous sponsor decals.

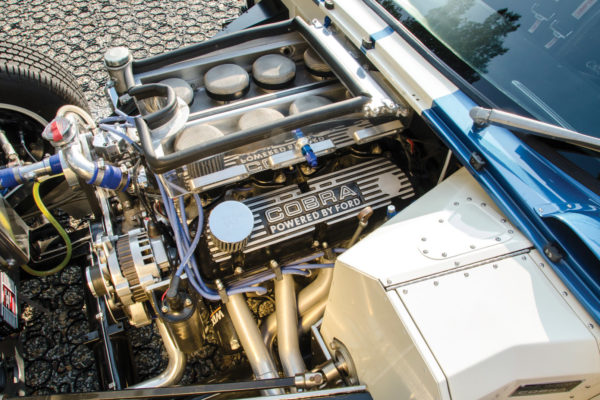

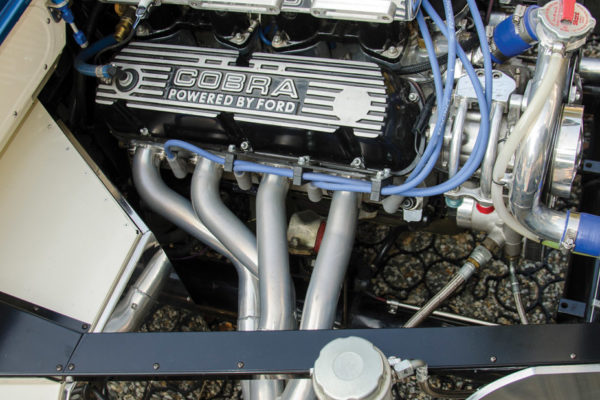

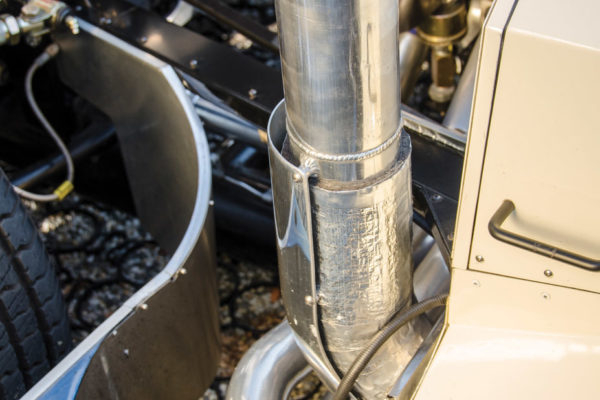

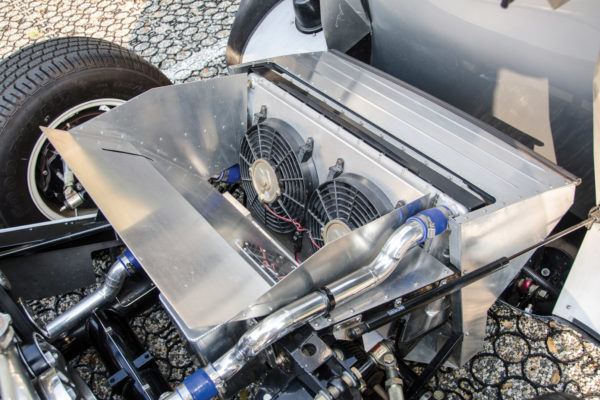

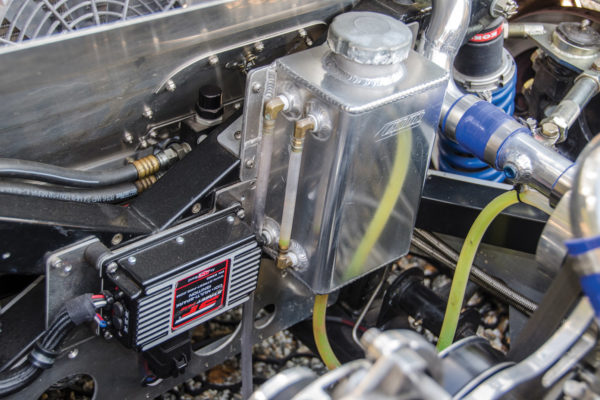

In the engine compartment, I took some liberties for the sake of driving comfort by adding power steering, air conditioning, electronic fuel injection and lots of polished aluminum and stainless steel. Even with all these amenities, however, it is clear that this replica is a loud, brutal race car, not a comfortable cruiser. What follows are some hard-won lessons from my lengthy project.

Overall, I’d emphasize that perseverance is a requirement because most kits don’t just fall together. I had some serious setbacks during my 15-year build. The worst of these were the loss of my dear late wife of 40 years, and increasing responsibilities at our business in Silicon Valley that I founded with three friends in 1999. Through it all, I remembered that I had finished almost every project I’d started throughout my life and was darn well going to finish this one. So before embarking on one of these projects, ask yourself if it’s a realistic task for you, given current (and possible future) family and work responsibilities and financial requirements.

In terms of nitty-gritty details on this particular project, wiring was one big challenge. Even though I worked in the electronics industry, I had difficulty with the nuances of automotive wiring. Not the least of which was reading the tiny writing on the dozens of wires in my universal harness that came with the kit.

I got some initial help from a local hot rod shop but it went out of business, so I was on my own again. I asked around with some of my Cobra-building friends, and one name came up repeatedly: Glenn di Orio. He was an early Factory Five roadster builder who had decades of experience in all aspects of automotive maintenance. This gentleman has been a lifesaver for me not only on wiring, but on many other parts of the build. Experience really helps, particularly when the person is of high integrity. (That wasn’t the case with a couple of suppliers, but that’s another story.)

Several years later, I traveled to Southern California to visit the shop that was supposed to paint my car. It was well worth my time and expense, as my high expectations were exceeded. Jeff “Da Bat” Miller of Miller Customs in Temecula does great work and manages his cash flow well.

My decision to add EFI also posed some difficulties. Very early in my build, I purchased a well-regarded aftermarket EFI kit, which included the ECU and its huge, general-purpose wiring harness to go with my individual runner (stack) induction system. During the long build time, however, this product was discontinued, and it was also best tuned by an EFI expert. Even with years of experience building racing karts and a Devin in my earlier years, the job simply wasn’t for a mere hobbyist such as myself. I did use the system during the car’s first few thousand miles and it worked fine, but I have since changed over to a Holley system, which has a much wider following among both professionals as well as hobbyists.

My advice here is if you’re planning on using EFI, wait before committing to a system. You can get a good idea of how to lay out the components during your build by viewing friends’ systems or reading forums.

Another hurdle I had to overcome early on in my build was an engine I naively bought from a young local guy. He turned out to be not only a poor engine builder, but also unethical, and I would have been far better off buying a short block or crate motor from a reputable builder or Ford Performance.

From the first 30 seconds we ran the engine, I knew it had balance problems in the 1,800 to 2,200 rpm range. After driving it for only a few thousand miles, I pulled it and took it to Robert Cancilla, a reputable builder in San Jose. The engine was so poorly balanced, that nothing was salvageable from the short block but the rods. Robert rebuilt the engine, and I now have a 400 hp, correctly balanced power plant that revs up like a sewing machine. Lesson learned.

As for other buildup parts in general, I highly recommend McMASTER-CARR. Simply put, this industrial supply organization is the best I have ever dealt with. My car is loaded with hardware and other stuff from its catalog.

All told, my diverse background in microwave test instrumentation and racing sailboat hardware came in handy on this project. The common denominator: Products must be able to be shipped around the world and perform reliably to specification in harsh environments over long periods of time. In my Cobra replica project, I have sought to incorporate what I learned in these businesses. As noted above, I hit a few bumps along the way, but have done my best to overcome them in making a nicely finished, reliable vehicle that does justice to the remarkable legacy of the legendary Cobra Daytona Coupe.

Comments for: Memory Lane

comments powered by Disqus