Recipes for making big-block power in a small-block Cobra

Story and photos by Steve Temple

The original Shelby Cobras were blessed with a wide range of engines starting with Ford’s then-new 260 ci Windsor V8, and soon after it, the enlarged 289 ci version. From there, both the 427 ci and 428 ci FE big blocks marched into the horsepower parade, and Shelby was known to experiment with forced induction and some other power plays as well.

Those cast iron legends are still revered and potent today, but the replica market has created an explosion of variety, where just about anything is fair game — as long as it provides plenty of tire-frying torque. All sorts of engines have been fitted between the fenders, taking advantage of the latest power adders and dyno room tech.

In keeping with that trend, we came up with a short list of different motivational exercises to give prospective builders of Factory Fives (and other makes as well) some drivetrain ideas. These are far from all the possibilities used since the company first started out with the Ford 5.0-liter back in 1995, but they are a few nice examples of small-block Cobras you’ll find on the street today.

Takeoff Instructions from a Retired Air Traffic Controller

According to his parents, Phil White has been a gearhead since he could crawl. In fact, Phil wore off the hard rubber tires on several pedal toys before he even entered kindergarten. That led to customized bikes and later on numerous cars, trucks, motorcycles and a speedboat. But one vehicle in particular tops every one of them.

“All pale in any comparison to my Cobra,” he points out. “There are many reasons why, but how many people can actually say that they built a car and are then actually comfortable driving it? Think about that for a moment. I assembled it, sweated over it, tightened every bolt and nut, fretted over it and in the end was solely responsible for its roadworthiness! I mean, not only did I build it, but I drive that car hard. And I enjoy it every time I get into it!”

After doing some careful research, Phil purchased a Factory Five back in August 2002, and after a few delays and interruptions, completed the build by September 2004. The engine he eventually installed (after experimenting with a 302) is a Ford 351 Windsor block, punched out to 410 cubes by DSS Racing of St. Charles, Illinois.

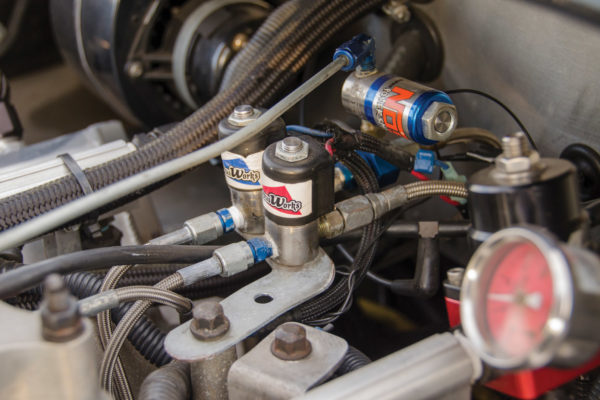

That was just the beginning, though, as he then opted for a combination of nitrous oxide systems from Nitrous Works and NOS Nitrous Oxide Systems. All in, the final output at the wheels is 635 horses.

The short block is a race-prepped DSS Super Pro Bullet with a Level 20 CNC block upgrade, as well as a main support system and windage package. Other upgrades include AFR 205 cc Outlaw race heads topped with an Edelbrock Super Victor 351W electronic fuel injection intake and a Wilson Manifolds billet intake hat.

For this power level with nitrous, a high-end fuel system was required. An Aeromotive A1000 pump supplies Precision Turbo 65-pound injectors with an Aeromotive fuel regulator to keep pressures in check. Air is supplied by an AccuFab 75 mm throttle body through a C & L Performance billet 80 mm mass air meter.

Other performance upgrades include a Canton Racing Products 10-quart circle track oil pan, Meziere Enterprises 55 gpm electric water pump and Ford Performance high-volume oil pump. ARP hardware was used throughout the build.

The engine was assembled by Jason Fields of RJ Performance in Sharpsburg, Georgia, in early 2009. When it was installed, Phil also upgraded the transmission to a TREMEC TKO 600 with a McLeod Racing SFI-rated bellhousing. To make everything fit, the drive shaft had to be shortened to the length of a beer can. To have more options and better brakes as well, Phil also upgraded all four corners from four-lug to five-lug wheels.

All told, this setup boasts 629 lb-ft of torque at the rear wheels. Even though one drag strip told Phil his car was “too quick” for the 1/4-mile (since it doesn’t have all the required safety gear), he whipped through the 1/8-mile in 6.646 seconds at 108 mph. That’s one exhilarating takeoff!

Father-and-Son Project

Jason owns an auto repair shop, RJ Performance, which conveniently enough works on Ford vehicles primarily. This includes diesel pickups, but he also does high-performance work on Blue Oval cars and has raced a 5.0-liter Mustang as well. After working on the engine for Phil’s Cobra (also featured here) and tuning the car on the dyno and on the track, he had an epiphany: “What a great project this would be for myself and my son Jordan to build together as a father-and-son project!”

Jason took delivery of his Factory Five Racing Cobra in 2012, but like Phil’s project, he encountered a few delays along the way, as his young son Jordan’s athletics and other activities took priority. Like so many kids his age, “It was apparent that his focus and interest levels weren’t quite there yet.” Well, that’s what dads are for, right?

Finally, a little over two years after they started project, work resumed in earnest in January 2016. Meanwhile, the engine build took place at RJ Performance, where Jason started with a DSS Super Pro Bullet short block with very similar specs to the mill in Phil’s car. There’s one big difference, though, as Phil had elected to boost power with a Vortech S-Trim centrifugal supercharger.

The belt-driven supercharger is set to run at 12 psi, boosting final output to 554 hp at the rear wheels. To keep up with the enhanced airflow, the fuel system employs an Aeromotive A1000 pump and Precision Turbo 65-pound injectors. Actuating the Ford Motorsport roller-rocker valvetrain is a nitrous-specific COMP Cams 35-556-8 bump stick. Downstream from the combustion area are BBK 1 5/8 long-tube headers, which bolt directly to the ceramic-coated Factory Five side pipes.

They finished the build in April 2016, and Jason drove it in primer for a few months before removing the body and sending it out to the paint shop in June 2016. Since Jason is not a painter by trade, “A big thanks to my friend Billy Vickery and B & B Body Shop,” he says. “We reassembled the Cobra the final time in July and August 2016 and have been enjoying it ever since.”

That included a road trip to the London Cobra Show in June 2017, where he met up with Phil and his son Jake. So this father-son weekend getaway actually was a joint event for all four of them. Hanging out with like-minded Cobra folk always makes for a great time, especially with two great replicas related by blood.

Overkill Cobra

Scott Young started building models cars at the tender age of 10, so some might say he was born into the hobby. His father was the general manager of what was the largest Ford dealership in Northern California at the time. But in 1966 he bought a Dodge dealership in the Oakland area, and they were no longer a Ford family. Even so, Scott remembers the day in 1967, during his senior year of high school, when he walked into a Ford dealership in Walnut Creek and saw his first Shelby Cobra. It was blue with white stripes, and from that moment, the love affair began.

Over the next four months, he was in the dealership at least twice a week to look at it and dream about owning that very car. But with a sticker price of over $6,700, it seemed only the rich could afford it. Keep in mind that a new Ford Galaxie 500 stickered for about $3,500 back then.

In the ensuing years, Scott bought and worked on a few different makes of performance cars, but his love of the Cobra never diminished. Scott always had framed pictures on the walls of his office or at home, and he dreamed about owning one of these special cars for years. Finally, a friend told him about a build school where you would learn how to build a Cobra replica hands on. That is when he first learned about Factory Five, and he promptly signed up for the first available class.

“I had always doubted that a ‘kit’ car could live up to the legend of the Shelby Cobra,” Scott admits. “And I was not sure I would want to build something that came in a kit.” But the build school changed his mind on all of that. After only three days, he watched the car his class had built racing up and down the parking lot.

Upon seeing this result, “I knew I wanted to build my own and know that I had made it mine. I wanted to put every nut and bolt on,” he says. “The only thing I did not want to tackle, however, was the engine.” It had been many years since he had built an engine, and he was looking for something special. His goal was around 550 hp and a ton of torque.

“There are a lot of good engine builders available, and I researched several,” he recalls. “As a follower of the Factory Five Forum, I felt I wanted to go with someone that is familiar with these particular cars. I wanted to use one of the supporting vendors. I like that they followed the forums, and when someone had a problem, they would jump in and help.”

One company name that Scott kept coming back to was Gordon Levy Racing (now renamed LR Classics). After having several conversations with Gordon, he agreed to build my beast. “What a engine he built,” Scott says. “Nothing less than spectacular. With 570 hp, it is super quick and very easy to street drive.”

Gordon notes that even though the engine build was tailored for public thoroughfares, “It’s pretty much overkill for most street guys,” he notes. “You could take it on the track and race the piss out of it and not worry about it.”

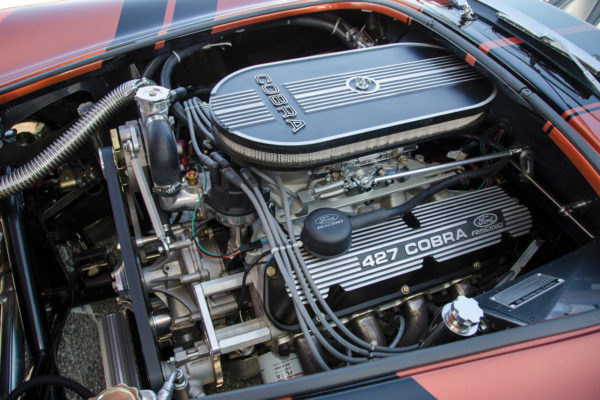

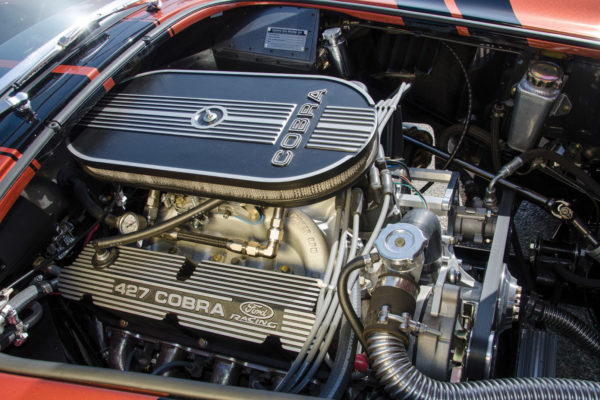

Gordon offers a wide range of performance crate engines from a basic 302 to full-on race mills. For this particular application, he started with his Stage 5 408 (550 hp and 540 lb-ft), but enlarged it to a 427 cubes.

“It starts with a 351 Dart, a hardcore little short block,” Gordon notes. Then he punches it out with a 4.00-inch stroke and 4.125-inch bore. No extra clearance is needed on the SCAT Enterprises forged crank for the alloy I-beam rods, but he does prefer using smaller Cleveland main bearings, measuring 2.750 inches. He’s found they live longer at higher revolutions per minute, while the larger 3-inch Windsor bearings generate more heat. In addition, the compression ratio was bumped up from 9.8:1 to 10.2:1, and he says the RaceTec 17 cc dished pistons that he installed have a better flame travel and quench.

As for induction, Gordon ordered a custom-spec Racing Head Service 215 cc cylinder head with a COMP hydraulic EFI roller cam, even though the engine has a Quick Fuel Technology Q-series 750 cfm carburetor. He notes that an EFI street grind provides more vacuum, and the longer lobe center doesn’t affect power. It sits atop an Edelbrock Performer RPM intake with some minor port matching (the Victor Jr. unit is better for top-end competition performance, he adds).

Scott brought his bare chassis to Gordon for the engine install and a couple days of sorting on his TKO 600 road race transmission. Fifth gear on this particular drivetrain has lower ratio (numerically higher), so it’s more useable for acceleration, even though it buzzes a bit more in overdrive (at 5,200 rpm in fifth gear, it pulls like a fourth gear).

Once all that was done, next on the list was body and paint. At a car show, Scott came across a Cobra painted like a P-51 fighter plane. He inquired around and found out the painter was a guy named Jeff Miller, a familiar name on the Cobra forums.

“The original color I wanted was silver with gray stripes,” Scott relates. “The only problem was that it didn’t really talk to me. It didn’t say anything or make a statement. I searched and looked at every picture I could find and finally settled on the copper and black.”

To stay with the same color scheme, Scott also coated the side pipes and wheels in black as well. While he appreciates just about any color combination on a Cobra, “When I look at my Factory Five Racing Mk4, it talks to me: ‘Take me to the track and run me hard. We will have fun!’”

Overall Observations

Looking at these three small-block-powered Cobras, what sort of tech tips can we glean? After all, engine technology has come a long way since the days of the big-block Cobra. While that beefy engine looks impressive stuffed between the frame rails of a roadster and makes wonderful power, it adds a lot of weight. An aluminum block can offset that, but at a substantial increase in cost.

Which brings us to the virtues of the stroked small block. This type has now become the engine of choice for most Cobra roadsters (and a number of other project vehicles as well). Why so?

Package size, for one. Fitting it into the engine bay of a Cobra is much easier, and the weight is substantially less. This latter aspect makes for better handling, whether on the street or a road course. And by stroking the block, the torque gains can be significant, supplying plenty of punch when coming out of a curve.

Another aspect is cost, and good engine builders are pulling big-block numbers out the small block for far less coin. For added thrills behind the wheel, there’s a plethora of power adders out there for the small block. Nitrous is a real hoot, as noted in Phil’s Cobra, but admittedly the tank does take up the limited amount of space in the trunk. As for supercharging, the Vortech centrifugal unit in Jason’s Cobra has the advantage of a smaller size than a Roots or twin-screw blower, although either can be made to fit on a small-block without cutting up the hood.

Whatever sort of mill you use, you should also consider EFI for optimizing the fuel flow to work in concert with the increase airflow. Fortunately, a number of EFI systems on the market are tailored to small-block applications. In that case, you get the best of both worlds: the improved driveability of EFI along with the potential for big-block power levels. What’s not to like?

Comments for: Power Plays

comments powered by Disqus