Sundowner Corvette Bonneville

By Steve Temple

PHOTOS BY STEVE TEMPLE, Courtesy of Banks Power, and Popular Hot Rodding

Standing solemnly on the Bonneville Salt Flats at sunset, actor Sir Anthony Hopkins uttered a classic line in one of the best motorsports films ever made,: “This is sacred ground.” He was effortlessly portraying speed-bike racer Bert Munro in The World’s Fastest Indian is based on “One Hell of a True Story” (as boldly proclaimed in the movie’s promo poster).

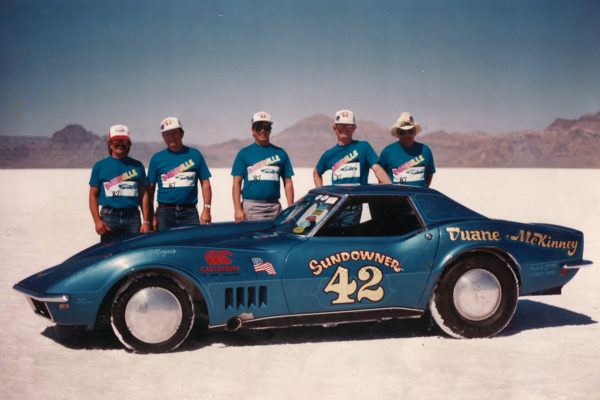

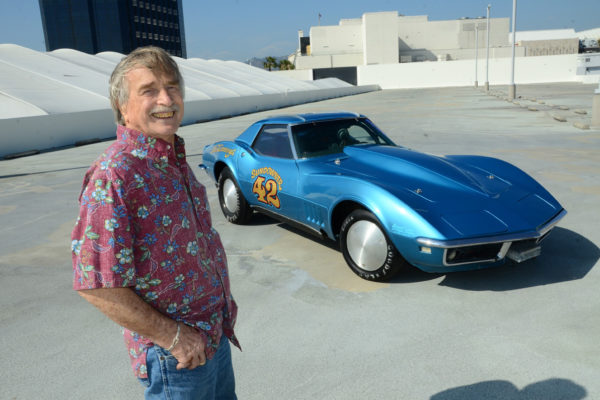

Anyone who’s come close to joining the 200mph club can relate. Just ask Duane McKinney, who drove a ’68 stock-bodied Corvette to a record-setting 240 mph!

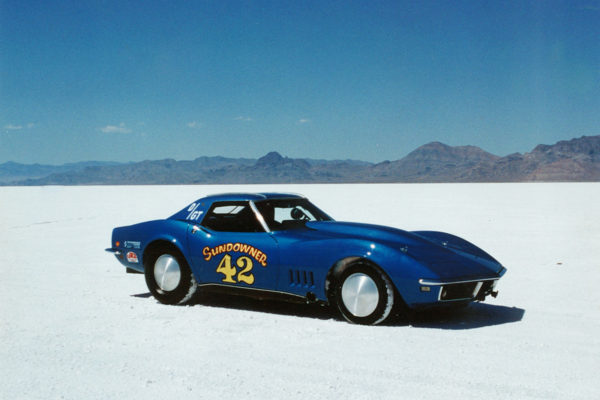

What makes this achievement all the more remarkable is not just that he set other records as far back as the mid-‘70s. Realize, too, that it was in a stock-body passenger car. Running a production-series, iron-block V-8. On pump gas. Naturally aspirated, too. Not only that, the trannie was a four-speed. All told, this achievement was like breaking the speed of sound in a wooden sailing ship—with its oars still in the water.

That’s because as sleek as the C3 looked, its aerodynamics were actually a step back from the C2, the first Corvette to ever have its lines refined by wind tunnel testing. For proof, take note of an intriguing article in the May 2009 issue of Corvette Fever. In a comparison of the aero characteristics of every Corvette body style from C1 through C6, the Cd (coefficient of drag) of a ’70 model was found to be as bad as the C1, even worse than a C2’s. So basically the ’68 body shape had only slightly better aerodynamics than a shoebox.

To be fair, these same wind-tunnel tests revealed that the addition of the tiniest rear spoiler did help produce 13.9 pounds of downforce in the rear, the only Corvette that was able to produce negative lift numbers. (Not counting the new 2014 Stingray, which has gone through extensive aerodynamic testing, as noted in our series on this new design.)

Even so, Corvette engineer Zora Arkus-Duntov wanted the Sting Ray's replacement (originally was slated to appear for the 1967 model year) to be smaller, leaner, and more aerodynamic, ideally with a rear- or mid-mounted engine. Designer Bill Mitchell, on the other hand, loved to make cars look aerodynamic, but not necessarily be so in reality. Ultimately, the C3’s coke-bottle curves were a victory of Mitchell over Duntov, of style over substance. And for all its failings, it also sold remarkably well.

Duane McKinney found an unsuspecting ’68 C3 on a used-car lot in February of 1975, and fellow racer Bob Kehoe drove it home, toward a much higher calling. The salesman probably would have ripped open his plaid sports jacket if he had known.

First, those problematic aerodynamics had to be addressed before taking it to Bonneville later that same year, where it hit 166 mph on a D/GT of 169 mph (??). Overcoming both drag and lift forces would be just as much or more of a challenge as building a monster of a big-block engine.

Breaking through wind resistance would come down to a matter of brute force, one that required the services of a seasoned engine builder who knew more than a thing or two about hurtling over the Salt Flats at ungodly speeds—sacred ground or otherwise. But that individual would have to wait.

First, McKinney had to figure out how to avoid an unwanted takeoff from the flats was crude yet fairly effective: lead. Lots and lots of lead. Everywhere you look—under the nose, behind the seats, in the back end, he added thick, gray plates, stacked like pancakes at a VFW fundraiser. And to make sure the car wouldn’t skitter around like a shopping cart with wobbly wheels, the caster angle was increased using washers on the control-arm mounts to nine degrees. The front wheels had to track as straight as Tonto’s arrow.

After all, 200 mph on the Salt is no joke. It’s nothing like 200 mph in the quarter-mile (which is no joke either, but a wholly different scenario). We’re talking about miles at speed, not merely a few seconds. As for velocity, imagine covering the length of a football field in the time it takes to blink.

In addition to the aero issues already noted, there are traction issues, steering issues, and don’t forget engine reliability issues. Also, Bonneville is at a higher altitude, so you have to tune for air density, temperature, humidity, and so on.

Speaking of engine tuning, who cooked up the mill for breaking the double century mark? He would be none other than performance sage Gale Banks. While he’s mostly known today for an impressive array of upgrades for diesel engines, before he ever even touched an oil burner, he employed forced induction on gasoline mills to an extreme degree, along with more than a few other tricks. He can lay claim to a slew of land and marine speed records in several categories. Interestingly, it was the sale of his beloved ‘63 Corvette that gave him the financial means to open a much larger shop and begin selling performance parts.

Looking back on the project, which would eventually spent months and months in Banks’ shop getting breathed on heavily, “Duane prepped the car, got the whole thing laid out, but didn’t have it done,” Banks recalls. Given all the after-hours wrenching, along with the late-afternoon runs on the salt, the name Sundowner would be fitting.

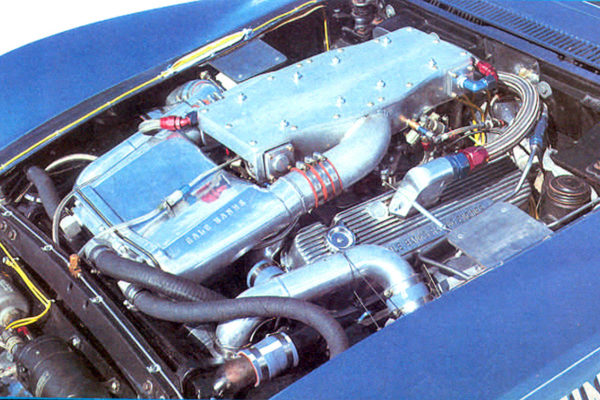

After some head scratching, he came up with a way to increase the air density—without a turbo. All in order to force-feed a single 4-barrel Dominator mounted on the single quad intake. It was fitted on a 430 block (.010 bore on a 427) with iron cylinder heads, and low-compression, 12.5:1 pistons. He started by cutting holes in the radiator to nose more air into the intercooler using carbon dioxide.

“The secret to CO2 is to put an expansion valve at the water inlet,” Banks explains. “That way it stays liquid up to the valve, and the orifice limits the max flow rate.” That would lower the intake air from as high as 105 degrees down to 40 or even less. And for every 10-degree drop in temperature, he points out, there would be a one-percent increase in air density.

But this single device didn’t solve all the problems. A one-inch rubber hose that dumped CO2 underneath the car would freeze and crack, then break off. So the race crew had to scrounge around Wendover, UT to find an elbow of electrical conduit that could withstand the low temps.

Another challenge caused by the chilling was icing up the carburetor, mounted inside a custom-fabricated pressurized plenum. The engine wouldn’t run until it heated up, so they didn’t turn on the CO2 until Third gear.

Once all those hurdles were overcome, “It made great power, ran 210-plus,” Banks notes, referring to records set in ’76 and ’78. “That was with no turbo, just intercooling. It was the fastest single-barrel Corvette on the planet!”

For all its success, though, the Sundowner was capable of even more. Even though Duane was now a card-carrying member of the 200-mph club, he was not content to rest on those already impressive runs. Fortunately, Gale Banks was certainly was no stranger to the Salt Flats, having campaigned a Studebaker there in ’78 and ’79.

“At the time, most ran in the low 200s with blown Chryslers.” When the Studebaker cracked the 232 mph, “That woke everybody up!” (Along with the fact that they had to make badges for rear window of Studebaker for spinouts at speed.)

Having developed a taste for more salt, McKinney again paired with Gale Banks in 1982, but this time with big-block puffed up with a pair of AirResearch TEO691 turbos on a Offy heads (which had already been used on meth-fueled Indy cars.)

But these windmills, fitted with massive, three-inch wastegates, wouldn’t do the job right out of the box. While they could deliver as much as 1700 horses at sea level with a whopping 23 pounds of boost pumping, the best initial runs at Bonneville were “only” 220. Once more, Banks faced a challenge requiring some hot-rodder’s ingenuity.

For an answer, looking at air density was again the key, but this time from a different perspective—an elevated one, literally. Realizing that the altitude is more than 4200 feet at Bonneville, the engine was toiling where the air is thin. Banks advanced the spark timing four degrees to compensate for the slower flame front.

In addition, he did away with the CO2. Since it’s less effective than water for heat transfer, he switched to a chiller filled with ice water. “Running gas doesn’t absorb heat as well as mass,” Banks points out. “Ice water especially. It absorbs a huge amount of BTUs.”

For all the serious efforts that went into launching an attack on the barriers to top speed, there were a few moments of levity. After some blistering passes, Banks lifted open the lid on the chiller, and discovered something totally unexpected: a little yellow rubber duck. “What the hell?” he laughed. Turns out the boys had dropped it in there for a joke. (And it remains there to this day, serving as sort of a good-luck charm.)

All these upgrades did the trick—toy duck included. In 1982, Duane set a record of 240.738 mph in AA/BGT, making the Sundowner Corvette the fastest stock-bodied, door-slammin’ passenger car in the world. Ironically, in doing so, it took the record away from “Hanky Panky”, the Studebaker also powered by a Banks’ turbocharged engine.

Even more records would fall over the next decade. The car sat idle until 1990, when Jon Meyer and Rick Head asked Duane if they could bring the Corvette out of retirement. At the time, Duane was involved in working with Glenn Deeds and driving the four-wheel drive ‘29 Ford roadster, so he was excited to see the Sundowner lick the salt yet again.

Once again the shiny little car began to make history . Rick Head set a class?? record of 187.082 mp. And 2000 was a busy and successful year for the car as first Rick gained entry in the “Dirty Two Club” at 220.238. Two days later Jon set a record of 227.787, also putting him in the club.

The following year also saw more records fall to the Sundowner, as Rick Head ran 203.889 and Jon Meyer ran 209.819 at El Mirage, both becoming members of the El Mirage 200MPH club. Later in 2002 Duane set a Record at El Mirage also getting in the El Mirage Two Club.

The latest record set was set by Duane’s son Dave at Bonneville with a speed of 251.838 in Aug of 2010. All told, 13 records were set at Bonneville and El Mirage, 10 of them were over 200 mph. Five members in the 200 mph Club and three members in the Dirty Two Club. The Sundowner was inducted in the Dry Lakes Hall of Fame in 2002.

Fitting indeed, then, to see the Sundowner on display in the lobby of the Petersen Automotive Museum for celebrating the 60th Anniversary of the Corvette. While the new Stingray was the star of the show, it stands on the shoulders of a land-speed giant.

Comments for: SALT SHAKER

comments powered by Disqus