’67 Sting Ray With Modern Mechanicals

By Steve Temple

PHOTOS BY STEVE TEMPLE

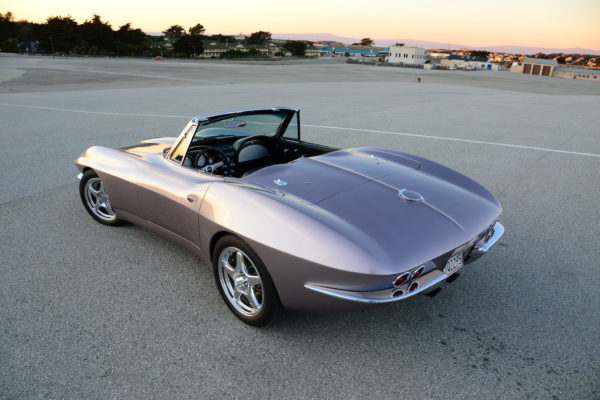

While everybody has been going ga-ga over the latest Corvette Stingray, here’s another route to consider: Why not take a ’67 Sting Ray and bring it forward? That was the path pursued by Dr. Barry Long, owner of the substantially modified Mid Year Corvette shown here. He conceived, managed and orchestrated the project, since he has a lot of hands-on experience working on cars before and during his years of medical training.

As a car-guy first and doctor second, Long’s concept was simple: “I’ve always wanted to build a Corvette on an original chassis but with an upgraded suspension and engine,” he recalls. “But have it still look like a classic. I didn’t want to build a hot hod.”

He enlisted the aid of Joe Calcagno, a Bloomington Gold judge and C1 Corvette Specialist who had tracked down a ’58 donor for an earlier restomod project. It featured a ’96 suspension under the three-inch wider rear fenders, along with a Grand Sport LT4 and six-speed. Now Long asked him to locate a suitable Sting Ray to fulfill what he envisioned.

As Long’s builder and co-conspirator Alf Ebberoth explains, “We wanted to build a ‘67 Corvette that was radical, but still looks like something the factory could have produced, if faced with the challenges we were up against with the body modifications.”

As with the ’58, they wanted to fit fatter tires in the rear without merely grafting on fenders flares. Yet the hurdles were even greater, because amount of widening would need to be about double what had been done before, while making sure the body lines would flow together in an integrated way. Also in keeping with the ’58 project, they planned to use only Corvette parts wherever possible (yet not necessarily from the same model year).

Sounds simple in theory, but the devil’s in the details. Fortunately, Long had already been to Hades and back with his ’58. When asked what the biggest difficulty was in his ’67 project, he noted that he had already overcome it in the ’58 when combining old and new components, along with enlarging the quarter panels. Even so, his “Air Roadster” as he dubbed it, “was a long ordeal,” Long admits, requiring many years of off-and-on effort.

At the outset, Calcagno came across worn-out ’67 with a dour drivetrain, driven hard and put away wet in a shed. Yet this platform was ideal, since using a generic, garden-variety vehicle was important to Long.

“I didn’t want to destroy a restorable classic,” he points out, as he’s acquired several originals (including a ’70 ZR1 and a ’90 Guldstrand) over the years and has a respect for the Corvette legacy. All told, the only items worth saving were in the cockpit, which were sold to help defray the cost of buildup. And as we’ll see, Long had some special custom touches in mind anyway for the interior.

First, though, he sought out Paul Newman of Newman Car Creations to install a fresher driveline and suspension. “The ’95 ZR1 is my favorite,” Long says. “That 32-valve, overhead cam engine is really something special.”

Enhancing it further, Ebberoff fabricated a custom intake and exhaust, and added a DeWitts radiator with dual fans. (This improved airflow is a theme we’ll return to shortly in other areas of the car.) A ZF six-speed from 1995 Corvette ZR1 funnels power to the 3:45 ZR1 rearend. In one of only a few exceptions to the “Corvette parts only” rule, the 1996 Corvette Grand Sport brakes were fitted with Baer’s Eradispeed stainless rotors.

But how to get the polished ZR1 rims and beefy BFG rubber to tuck under the wheel wells? After all, the factory track-width of a Sting Ray is actually slightly narrower in the back than the front, the reverse of what one might expect. To broaden the beam without tubbing the frame, Ebberoth split the fenders lengthwise and spliced in a six-inch section of fiberglass, bonding it in manner similar to the original manufacture of the body. For adding those curvaceous lines, he glued sections of surfboard foam to the entire side of car and then started shaping them so they flowed with the rest of the body.

This integration of the form was key to achieving the right look. “Every body panel required modification,” Long notes. At the nose, Ebberoff crafted new lower sections of the front fenders, extending from the bumper to door, with no air intake behind the front wheels. And new rocker panels cover the frame rails on the sides, under the doors. Also, the new fenders cover more of the wider new front tires (BF Goodrich 255/40ZR17, while the rears measure 315/35ZR17).

New door skins were also fabricated out of composite so they fit with the reverse curve of the mid-section, akin to the wasp-like waist of the C3. The resulting form seamlessly blends elements of C1, C2, C3 and C4 designs.

Once the foam was shaped to Ebberoth’s liking, he pulled molds off each panel and then made up the new panels in fiberglass, removed the foam and original panels and installed the custom-made pieces. (By the way, he saved the molds, in case any Car Builder enthusiasts want to save some time and effort when fitting big meats on a Sting Ray.)

Ebberoth also reworked the soft top’s cover panels by creating a small raised nacelle behind each seat, along with a smoother “waterfall” section between the seats (similar to what’s seen on Corvettes both before and after the ’63 to ’67 era). Even the door handles are blended into the body lines, using C5 pieces. Last but not least, Ebberoth drew on his Swedish training in metalworking to stretch and hammer the bumpers to fit the widened body parts.

Interestingly, the inspiration for the Air Roadster’s fluid, aerodynamic quality is not purely aesthetics. It also stems from Long’s background as a private pilot and airplane owner, and also his medical practice in addressing breathing problems. Altogether, he appreciates the subtleties of smooth airflow, and made sure the center console was streamlined into the back deck.

Yet for all this body shaping, one of the most challenging aspects was actually a fairly small matter: figuring out a way to secure the shoulder mount for the three-point seatbelts. It was eventually solved by fabricating a tiny part out of aircraft titanium, secured to the side mount for the convertible top. That way, there would be no clutter to distract from the Carrillo seats, covered in leather by famed upholsterer Sid Chavers. Other interior touches included Autometer Phantom Gauges fitted to the original cluster, Vintage Air A/C and custom power windows.

Once all the extensive body changes were complete, no ordinary paint would do. Long initially considered a simple silver, but his painters (Jose and Santiago Ramirez of Empire Restoration and Randy Reeds of Antique Auto Restoration) showed him a red metallic flake that would change depending on the light. In low light it looks bluish, even lavender, but in brighter light the hue shifts to a champagne color.

Long observes another surprising fact: when parked side-by-side with an original ’67 Sting Ray, “It’s amazing how similar they look together...Yet mine has the steroid boost it needed.” It’s as if famed Sting Ray stylist Larry Shinoda took the Sting Ray to its logical extreme—and then some.

Comments for: SMOOTH OPERATOR

comments powered by Disqus