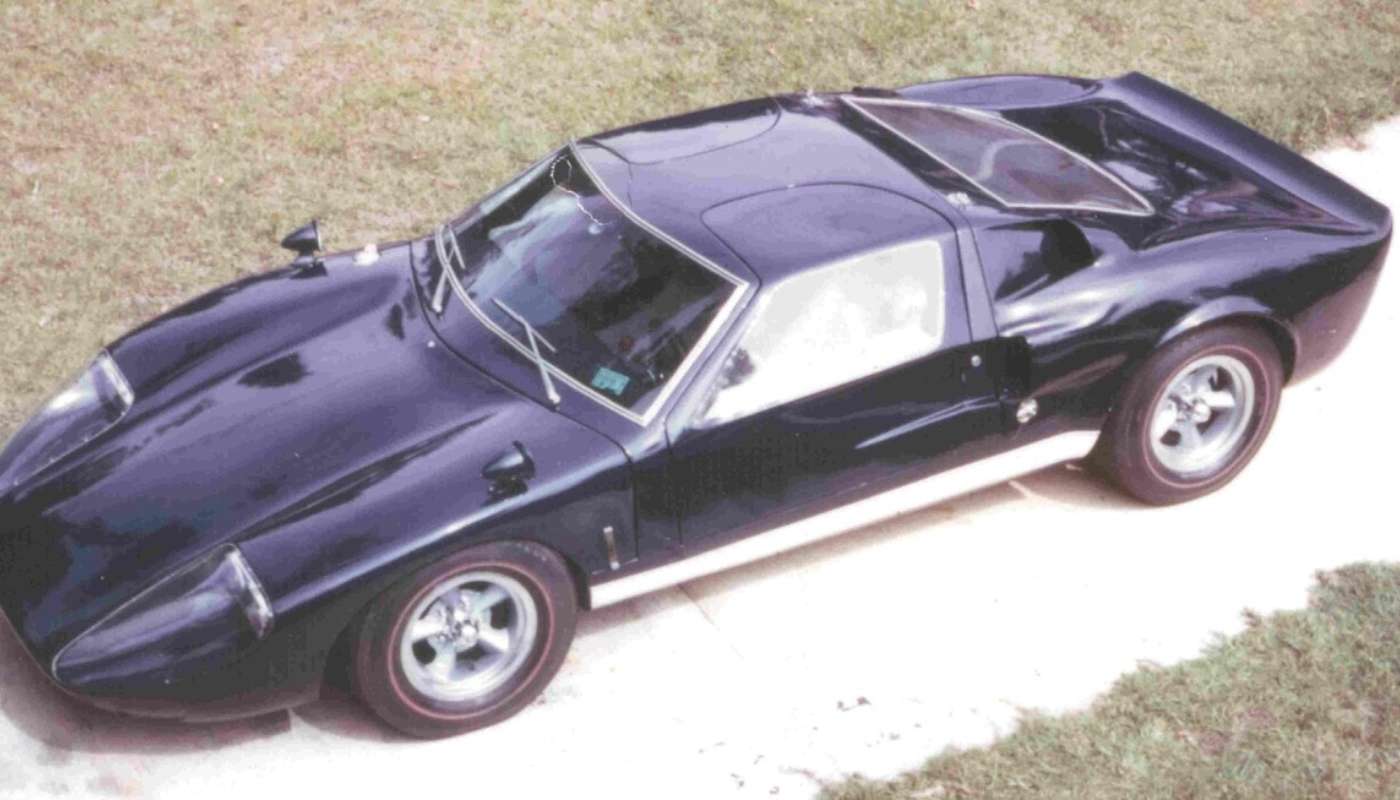

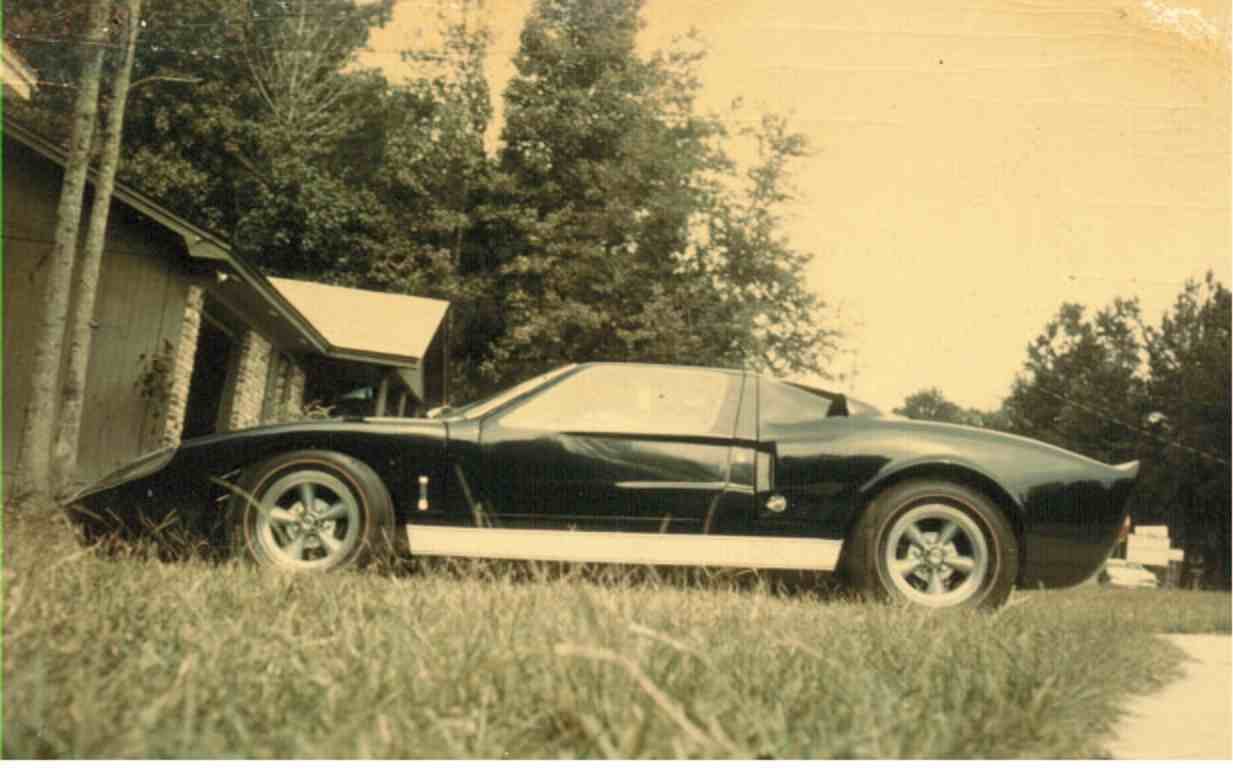

BUILDING A KELLISON GT40K IN THE '70S: Part One

**The following is a story about building a Kellison GT40 kit back in the 1970s utilizing a Corvair Corsa donor. The author is very thorough and there are few photos, but the account is an excellent view of what it was like building kit cars in the early days. The original text from this three-part story was taken with permission from www.kellisoncars.com.**

Story and Photos by Tom Piantanida

Chapter One: The Drivetrain

The Kellison GT40K is probably the closest I'll ever get to owning a Ford GT40. This rang especially true back when I was a graduate student raising a family on $8,500 a year, and the Ford GT40 camera car from Grand Prix was advertised for $6,000. I always thought (and still do) that the GT40K was a more accurate rendition of the Ford GT40 than the other pretenders, like the Fiberfab Avenger and Valkyrie, and the Sebring (although I never actually saw the Sebring in the glass so to speak).

Two iconic elements of the original Ford GT40 that I first saw on display at Watkins Glen in October 1964 were those distinctive doors and the sculpted air inlet on either side of the backlight. Unfortunately, many of the replicas lacked the GT’s distinctive doors and neither Fiberfab nor Kellison got the upper air inlets right. That was a disappointment that I dealt with on the GT40K that I built.

I acquired my GT40K in Houston in 1971 as a partially completed kit. It had an unmolested body on a VW pan, for which most of the Ford GT kits were designed. One exception was the Fiberfab Valkyrie, which required a tube frame. Included in the deal were a 1,200cc Volkswagen engine and transaxle, mag-style wheels and adapters, and BFG redline tires. A pair of high-back fiberglass seat shells and several small sheets of Plexiglas were stowed inside the car.

When a friend and I trailered the GT40K home, my five-year-old daughter took one look at the car and burst into tears. It took us a while to figure out that she was unhappy because there was no back seat for her to ride in; she figured that we were going to have to leave her at home when we went for rides. The GT40K filled most of the 40-year-old, one-car garage that was attached to the house that I rented with my wife and two daughters.

My first decision was that the 1,200cc VW engine had to go. Searches through high-performance VW catalogues, such as EMPI, quickly established that more power could be had by the usual hop-up procedures of increasing displacement and compression ratio, installing hot cams, Webers, headers, etc., But to get decent power from the bug, required cubic bucks. I opted for a cheaper way out — a Corvair flat-six with a stock displacement, more than double that of the VW.

I was able to buy a wrecked 1966 Corvair Corsa convertible at a low enough price that I could part it out (in my driveway, which the landlord hated), and wind up with a free 140 hp engine and a windshield. (The GT40K was designed to accept a 1965-69 Corvair windshield.) I traded the Powerglide for a four-speed Saginaw transaxle, and sold the rest of the car top mechanism, seats, wheels, tires, harmonic dampeners (Corvair convertibles needed them to control body torsions at some frequencies), etc., winding up with the desired items and a small profit.

The 140 hp Corvair engine didn't have many miles on it, but my next decision, which was precipitous, required that I rebuild the engine. I had decided that as long as the Ford GT40 was mid-engine, my GT40K would be, too. Engines don't care much about which way they rotate; in fact, the Corvair flat-six rotates the opposite way of most other American engines. Other than the starter, which gets the engine started off in the right direction, the only part that controls the engine’s direction of rotation is the camshaft.

Crown Manufacturing sold a reverse-rotation Corvair camshaft for people who wanted to power their dune buggies with the flat-six without flipping the ring gear in their bug transaxle, or someone who was bolting the Corvair up to a non-flippable VW Type 2 transaxle. Crown hadn't counted on someone like me, who wanted to mount the Corvair in the mid position and still use the stout 1966 and later Saginaw transaxle, which used the same size gearsets as the full size Chevy of that era.

When I had flopped the pistons to compensate for the thrust offset, inverted the engine louvers so that the crank wouldn't sling oil into the engine breather (yeah yeah, I know its a Corvair, and its supposed to sling oil), and installed the reverse-rotation camshaft, it dawned on me that needed a reverse-rotation starter. I called Crown Manufacturing for advice, and they suggested that I use a VW starter, which rotated the right way. But, of course, the VW starter doesn't fit. That prompted a three-month search for the elusive reverse-rotation Corvair starter.

Electrically, reversing the direction of the starter is simple, just rewire the brushes to the opposite polarity, but the real problem is that starters have an over-running clutch that transmits torque only in the direction of rotation. Ultimately, I found a Chris-Craft starter drive that was designed for a reverse-rotation Chevy V8. This starter drive would work if' I machined the internal spiral splines off the Corvair starter shaft and pinned the Chris-Craft starter drive (it has both internal and external spiral splines) in its place.

The first time I ran the starter drive out to the limits of its splines, it locked into place, and I thought that I had goofed severely. It turns out that engine torque releases the starter gear, which then slips back down the spiral spline. When I tried the starter on the reverse-rotation Corvair engine, it worked like it was a factory setup.

After starting the Corvair, the very next thing I did was to pen a letter to Crown Manufacturing to let them know that I could supply reverse-rotation Corvair starters. During the succeeding five years, I sold seven starters at a small profit, but every little bit helps when you're a student with a growing family.

Obviously, a Corvair engine is not going to fit on the pad of the VW pan where the back seat once rested. With much measuring and remeasuring, I truncated the VW pan just about where the central spine split into the two rear frame horns. I had calculated that a rear subframe attached to the pan at that point, would allow the use of the fully independent Corvair trailing-arm rear suspension and still maintain a wheelbase of 93.6 inches — more or less. The location turned out to be just right, but the cut was an unkind one, as I'll reveal further on.

The now-surplus VW engine, transaxle, wheels, brakes, etc. were turned into cash to promote the project. The rear subframe was going to be a bit of a challenge; I had no materials, no machine tools and no welder. I met the challenge by using surplus Unistrut to fabricate the frame, boxing the U-sections where necessary, and using the school machine shop and welder after hours. On those nights when I could use the shop, I fabricated subframe members one or two at a time, and carried them home. They lived in my bedroom, next to the Corvair windshield that I was protecting from two kids and a dog.

When I had all or most of the pieces cut and fitted, I would weld several pieces together, clean them, and carry the subassembly home. As the subframe progressed, the assembly got heavier and heavier — Unistrut is not the world's lightest material. Ultimately, I had to employ the services of the school machinist, who fortunately had a keen interest in the project. We eventually completed the subframe and I was ready to attach it to the VW pan, well, actually to a bulkhead that divided the cockpit from the engine bay. The finished rear subframe included spring pockets and shock mounts to accept the Corvair rear springs and shock absorbers, attachment points for the Corvair trailing arms, and the rear motor mount.

Normally the transaxle has a sheetmetal cover over the differential housing, but for this application; I made a new cover of plate steel. The plate would lie flat on the differential housing and be bolted to it using the normal attachment points. To this plate, I welded a vertical L-shaped bracket that hung from the crossmember and was isolated from it by rubber mounts.

Because Corvair cylinder heads are symmetrical and can be interchanged, the same is true for Corvair headers. I was able to use aftermarket headers by swapping them side-to-side, leaving the collectors facing the rear of the GT40K. A pair of glasspak mufflers completed the exhaust system. On the top end, I discarded the four single-barrel carburetors in favor of a central 390-cfm Carter AFB four-barrel carburetor on a tube manifold. Hydraulic master and slave cylinders from Neal Hydraulics actuated the throttle linkage. Another pair of cylinders operated the clutch.

Next time, we'll get into assembling the Kellison body, some of the modifications that were necessary to accommodate the Corvair drivetrain, and the process of undoing a few production compromises.

Comments for: BUILDING A KELLISON GT40K IN THE '70S: Part One

comments powered by Disqus