Making your Own Luck

By Karen Salvaggio

Photos by Marshall Autry

There’s something truly inspirational about an individual who makes a path for themselves in order to follow his or her dreams. Such is the case with Shelby American driver Allen Grant. Allen’s early years were spent on his family’s farm, far away from any racetracks, but the values he developed, including a solid work ethic, an appreciation for the rewards of hard work, and a fierce will to succeed, carried him to a world championship life.

As fortune would have it, Allen’s family relocated to California in 1942. His father worked in the Bay Area shipyards for a few years, before moving the family inland to the small town of Modesto after the war. Allen was still an adventurous youth at the time and discovered his penchant for cars through the 1950 Pontiac Catalina his father bought for him at age 16. But Allen was in California now, and soon found himself living at the center of the 1950s American car culture.

In Modesto, he joined a loosely affiliated group of young car owners and enthusiasts calling themselves “Ecurie AWOL” (ecurie being French for “race team”). It was during this time that Allen became good friends with another member of the club, future filmmaker George Lucas. While four years younger than Allen, their friendship left a lasting impression on George; memories he paid tribute to by modeling the character John Milner and his “piss-yellow deuce coupe” on Allen in the movie American Graffiti.

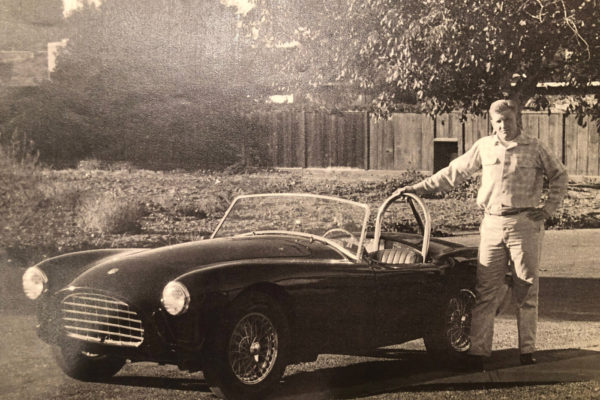

Wanting something more nimble than the unwieldy ’50s Pontiac he’d previously owned, Allen bought an Austin-Healey 3000 and soon discovered autocross and gymkhana events. He did well enough to secure class wins, but he wanted to make top time of day. The fastest car at the events was an AC Bristol, and soon enough, Allen sent the Healey down the road and added an AC Bristol to his garage. With a strong desire to win, Allen stripped the car down to the bare chassis and rebuilt every component — all with an eye toward maximizing performance.

A natural-born driver, Allen’s skills developed quickly, and as soon as he turned 21 (the required age to apply for a race license), Allen signed up for the SCCA competition school. As luck would have it, his instructor for that school was none other than his future Shelby Cobra teammate, Ed Leslie. Allen won 12 of 14 events in his first year racing (1962), earning him the title SCCA Rookie of the Year.

Even though Allen then enrolled in college, his thoughts always drifted to racing. When he read that Carroll Shelby had set up shop in Los Angeles and was planning to install small-block Ford engines in the AC Ace, Allen skipped school and drove down to Shelby’s shop in Venice, California, in order to offer his services as a driver. With Allen’s winning race record in the AC Bristols, surely Carroll would jump at the opportunity to have his talent behind the wheel of an AC Cobra. Or so Allen thought.

Upon arriving at the shop, his request to see Carroll was met with more than a small amount of resistance from Joan Shelby, Carroll’s office manager. Without an appointment, Allen was told that Carroll would not be coming in that day and that he’d have to come back another time. Not to be denied, Allen drove around a bit, then decided to go back over to the shop and wait out front. Sure enough, Carroll drove into the parking lot about an hour and a half later, and when he was about to enter the building, Allen stood in front of the doorway, not moving until he had the chance to speak to Carroll.

As anxious as Allen was to offer his driving services that morning, Carroll quickly extinguished that flame, flatly telling Allen, “I’m not looking for any drivers right now.” With legendary drivers such as Dan Gurney, Ken Miles, Phil Hill and Dave MacDonald already on the Shelby team, one might appreciate Carroll’s view at the time.

Yet, Allen was determined and seized the opportunity when Carroll then asked, “Can you weld?” Again, as luck would have it, Allen had worked as a welder in the past and jumped at the chance to work in the shop. He made it clear to Carroll though, and to engineer Phil Remington, his first supervisor, that his goal was to drive. Phil understood, and as soon as opportunity allowed, Phil transferred Allen to the race shop.

Months passed, however, and still no opportunity to drive. One day, Carroll approached Allen in the shop and informed him that he would be moving Allen upstairs to serve as production manager, where he would share an office with Peter Brock. Allen was leaving the race shop, a place he loved, to work more on the business side of the operation. It seemed his opportunity to drive an AC Cobra was quickly slipping away.

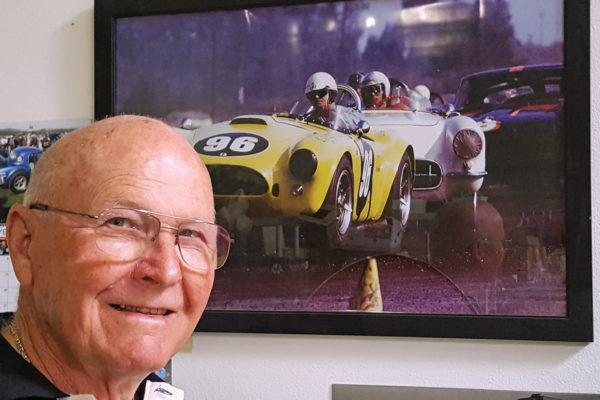

Allen again turned what seemed to be lemons into lemonade, using his position as production manager to broker a deal between Shelby American and Coventry Motors in Walnut Creek, California. The Coventry dealership had a race driver and wanted to field a Cobra, so Allen made the deal with them, but with one caveat — that Allen would drive the car. Coventry agreed and paid $8,000 for the car. George Lucas designed the paint scheme for the car, an eye-catching bright yellow with black diagonal racing stripes. Allen finally had his ride — albeit in competition against the very company for which he worked.

The team, consisting of mechanic Ole Olson, crew chief George, and driver Allen, named the car The Executor, to underscore what they were going to do to the competition. Allen prepared the Coventry Cobra to the finest detail, drawing from his experiences working in the Shelby race shop alongside legendary drivers and skilled engineers such as Dave MacDonald, who also prepared his own AC Cobra for racing.

Allen found success early. In Santa Barbara, despite being the sole Cobra amongst a field of hungry Corvettes, Allen won both races that weekend, as well as the next race at Candlestick Park. But it was the One Hour race for GT Cars held during the LA Times Grand Prix weekend at Riverside where Allen would have his first opportunity to race heads-up against his racing colleagues from the Shelby stable.

That race put Allen on the map as a driver. Competing in his self-prepared Coventry AC Cobra in the GT class, against the finest drivers of the day, stands even today as the most favored race of his career. Having been denied a seat on the Shelby Cobra team, he found a way through sheer will to get himself into a worthy ride. And he was now pitted against the very company from which he secured his daily livelihood.

With the factory Cobras driven by Dan Gurney, Bob Bondurant and Lew Spencer directly ahead of him on the front row, Allen was gridded in the second row next to Richie Ginther in a Ferrari GTO. This was Allen’s first race at Riverside, and his plan was to follow Dan around early to learn the track.

When the green flag fell, Allen blew by Bob and Lew, and was following Dan when he shockingly found himself spinning off the track at Turn 6, after seemingly being tapped by Bob. Allen watched the entire 30-car field pass before he was able to return to the track — in last place.

Facing a 45-second deficit to the leaders, Allen was livid. He became determined to pass everything and anything ahead of him. With the crowd of 50,000 cheering him on, and the race nearly halfway over, he came upon Dan’s wounded Cobra sitting alongside the track, and he knew then victory was within reach. When the checkered flag fell, Allen had passed every car and was a mere two seconds behind Bob, taking second place.

Still livid from the incident in Turn 6, Allen bolted out of his car, ready to tear into Bob. But his dad, his brother, and friend George told him that the crowd had gone wild watching him drive and that the only car the announcer talked about was Allen’s during the entire race. He was a star!

That single race secured Allen’s place as a truly worthy driver, capable of besting the greatest drivers of the day. The following years brought further success, and legendary drives. His contributions to the Shelby American team were many, including a prized victory at Monza, when he was paired with Bob against the Ferrari team. His outstanding performance at Sebring in the pouring rain, coupled with his teammates’ solid performances throughout the season, secured the necessary points to win the 1965 FIA World Manufacturers’ Championship for Shelby American. This was the first, and now 53 years later, the only time, an American car has won the FIA World Championship.

Allen retired from racing after the 1965 season, as Ford shifted its focus to the GT40 program and was looking for drivers that were more internationally known, Allen relates. He worked on the King Cobra for a time at the Shelby shop, until Carroll sadly informed him that he needed to sell the car. Allen decided to resume his college education, returning to his hometown roots in central California, and pursuing a successful career in land development and construction. His love for cars and motorsport has never relented though.

His stable of cars is housed in the workshop of Grant Development, located in the Palm Springs area. Recognizing he was in the middle of something very special early on, Allen had the wisdom to keep virtually everything associated with his racing world. His office is a glorious tribute to his racing adventures, filled with memories of good friends, and good times. It’s a showcase for trophies, awards, drawings, photos, and memorabilia, all of which documents every aspect of his racing life.

Some 53 years after his incredible adventures with Shelby American, Allen is a living example of what can be accomplished when you are committed to making your own luck.

Comments for: Making your Own Luck

comments powered by Disqus