MGB-based Hawk 289 Cobra replica

Story and Photos by Iain Ayre

Even though Cobra replicas strive to imitate the original, they all differ in the details. Consider the Hawk 289. While it runs a bit pricier than some replicas, the end result is a very high-quality car appreciated on the secondhand market. On the other hand, it’s possible to build one on a budget, as the body and chassis kit sell for about $9,800 (plus shipping and customs fees to the U.S.), and good donor engines are an option.

In addition, the use of a donor MGB does help save quite a lot on the build. Expensive items such as the axles, brakes, steering column and so on can all be bought as a package in a rust-doomed MGB for well under $1,000.

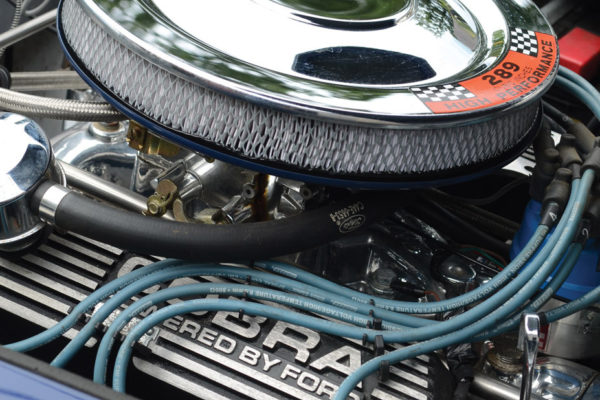

The choice of an American Ford V8 engine also helps to keep mechanical costs reasonable. It’s still possible to find a period-correct 289 ci V8 engine without breaking the bank, although the later 302 ci is essentially the same engine.

Stuart Clarke was very taken with the 289 Cobra many years back in an article. That authentic Cobra served as inspiration for his build, and he replicated it as closely as has been practical. But is a fiberglass-bodied kit car based on an MGB going to be anything like an AC Cobra, in real terms? The answer is emphatically, “Yes!”

For historical perspective, the AC Ace, on which the Cobra was based, was a stylish and spirited 1950s sports car. The Ace originally used the company’s own straight-six, designed back in 1918. AC finally replaced the geriatric engine with a Bristol six, but then Bristol ceased production of car engines. The optional Raymond Mays-improved Ford Zephyr six was unpopular with posh AC customers, and the prospects looked grim.

Then a Texas showman called Carroll Shelby suggested fitting the small-block Ford V8 with its light, thin-walled block casting, yielding double the horsepower. That concept snowballed into a legend, as the Cobra developed into a fat, scary monster with huge 427 ci big-block motors and bulging wheels and arches.

The Hawk is one of the few available replicas of the earlier and more subtle 289 Cobras, with skinny wheels and flattened wheel arches. The suspension on the AC was by single transverse springs at both ends, which was OK for its 2-liter engine, light aluminum body and twin-tube chassis, but not well-suited for dealing with serious power.

The same applies to the MGB’s axles and suspension. Like the AC, the MG’s suspension is quite good for its time, and even with basic V8 power doubling its performance, it doesn’t have any nasty habits lurking to bite you. The handling is stable and progressive, and while it doesn’t grip spectacularly well, it will give you plenty of warning before it begins to let go. There’s no snap oversteer or helpless understeer as with big-block Cobras, and the small-block V8 suits both Cobras and MGBs well.

The usual manual gearbox coming with a donor Mustang engine would be a T5, a strong gearbox with well-spaced ratios. With around 250 lbs-ft of torque available for a relatively light car, gear changing is to some extent optional: You can take off in second gear and go straight to fifth, and the car will grumble sleepily along at 1,200 rpm.

The Hawk’s chassis and body are both thick and substantial, and the car’s overall weight will be similar to an MGB, although the center of gravity will be lower. The light 289 ci V8 engine is actually only slightly heavier than the old-fashioned and very heavy B-series four. It’s also mounted farther back in the chassis, so again, the weight balance is quite like the MGB but rather improved.

The dyno-measured torque from Stuart’s V8 is 275 lbs-ft and 210 hp, so substantial power is on tap. It’s not too much for the MGB axles, though, as the Salisbury differential is the same for the MGB, the MGC, and the MGB GT V8. (That’s provided you avoid violence with the clutch, as the differential will comfortably handle a fairly standard 5.0-liter V8.)

If a much cheekier engine or rough driving techniques prove too much for the MG differential, a Jaguar XJ6 independent rear end can be bolted to existing alternative brackets on the Hawk chassis, and the Jag axle is pretty well indestructible.

The same applies to the front brakes. The standard MGB brakes will lock up the front wheels, as the car still weighs more or less the same as the standard donor MG. Bigger brakes do give you more control and better resistance against fading, so Stuart elected to go down a traditional British upgrade route and fitted Princess four-pot calipers. For more aggressive stopping power, the American Wilwood brand offers good value for money.

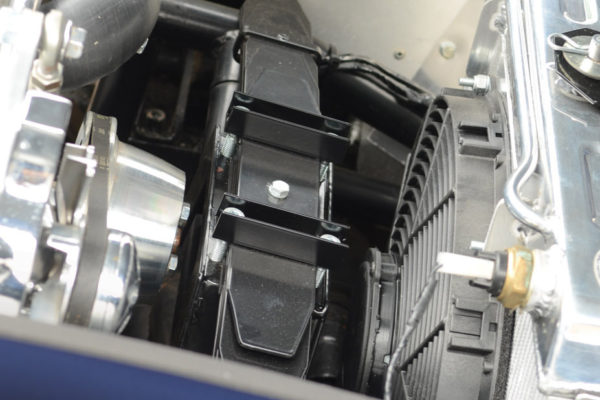

The original MGB suspension is an independent double wishbone, with the upper portion a lever-arm shock absorber. Even so, this unequal-length double wishbone setup is still a very satisfactory system. The MGB’s crossmember is discarded in the Hawk, but the rest of the donor MG’s front suspension and steering are used.

There’s also a Hoyle-designed independent rear suspension conversion available, or Hawk can supply anti-tramp bars (traction bars) and a Panhard rod upgrade for the standard MGB live axle. The sophisticated Hoyle geometry available from Hawk is definitely an improvement, but there’s no rush to replace a perfectly serviceable MGB front or rear axle.

Stuart’s engineering experience was initially academic rather than hands-on, and with the help of evening classes, he taught himself to repair cars, from which it’s only a small step to building them. In fact, with a brand-new chassis and body, building a car like a Hawk is probably easier than a restoration.

Most folks would agree that this is a charismatic, beautiful and tempting car. If you like MGBs, you will love the Hawk 289. It’s still a 1950s sports car — but with optionally scary performance.

Comments for: Bird of Prey

comments powered by Disqus