How Peter Brock improved on the original Daytona Coupe

Story and Photos by Steve Temple

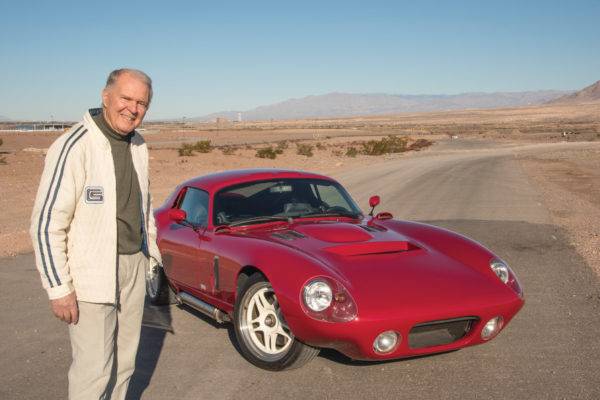

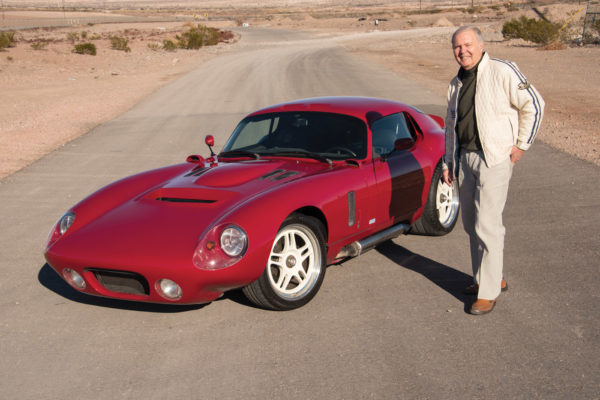

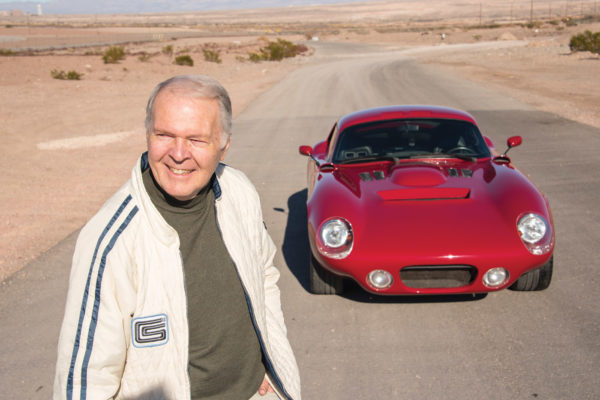

Any list of iconic cars from the ’60s would likely place the Corvette split-window coupe and Cobra Daytona Coupe at or near the top of the list. What makes them even more remarkable is the fact that one man, Peter Brock, designed both of them. Their stories have been told often in many publications — and in books written by him as well.

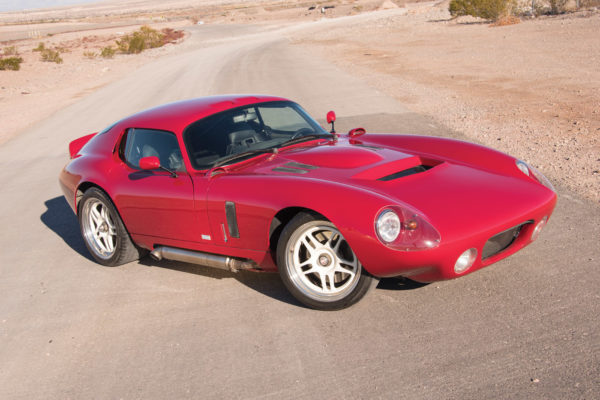

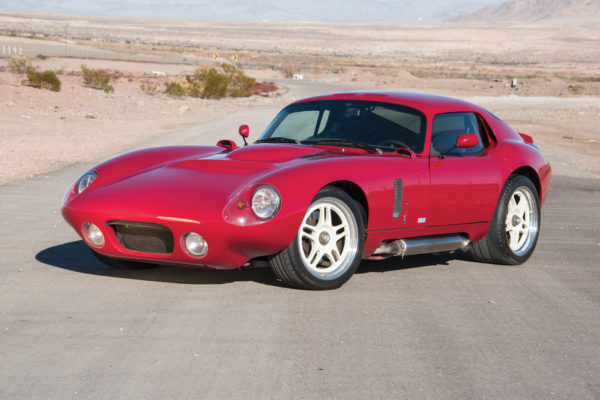

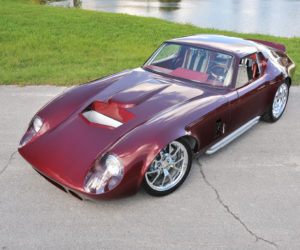

The latest chapter in his design career, however, is a clean-slate approach to the Daytona, a coup de grace if you will. Defined as a finishing stroke or decisive event, it seems a fitting analogy, as Brock’s refined configuration corrects a few of the Coupe’s manufacturing follies and amplifies aerodynamics and comfort as well.

The new Coupe is a replica of sorts, yet not entirely, since Brock is the car’s original designer. He has refined and enhanced the shape, so it’s more like an updated edition. The specifics of his aero treatments are of particular interest, as they are a driving force (literally) in both the original, and the car shown here. Brock initially gleaned these treatments from an obscure German textbook on the subject and applied the controversial topics to automotive design. With his latest iteration, Brock has even gone as far as to replace the traditional drivetrain to improve aerodynamics, as we’ll see.

Brock’s work on the latest Daytona began with a phone call back in 1999 from Jimmy Price of Hi-Tech Automotive (Superformance’s parent company). He wanted Brock to develop a Coupe in order to expand the company’s highly successful Cobra roadster line, but Brock admits that he initially turned up his nose, telling him, “I’m not interested in kit cars.” Jimmy tried to explain how Superformance builds production cars in a turnkey-minus form, but Brock still wouldn’t budge, not realizing the scope of the company’s operations.

So Jimmy came back a month or so later with a couple of airline tickets to Port Elizabeth, South Africa, in order for Brock to see the company firsthand. He came away impressed by the size and capabilities of Superformance and finally agreed to build a Coupe — but with a couple of conditions.

“The only way I’d do this is if we don’t do a ’37 chassis,” Brock told Jimmy. That of course refers to the antiquated John Tojeiro chassis with 3-inch main rails and transverse leaf spring suspension used in the original small-block Shelby Cobras. He also insisted on using former Ford engineer, Bob Negstad, the original chassis designer who worked for Klaus Arning on the 427 Cobra (the first chassis ever done on a computer, by the way).

Jimmy didn’t argue, as he was hiring two legendary figures in performance automobile design. Negstad’s involvement would also right a long-standing wrong in the original 427 Cobra’s development, which is an interesting backstory revealing some hidden tensions between Ford and AC Cars.

The latter company was a bit cheap, putting it bluntly, and prior to building the first 427 Cobra, AC had acquired some 4-inch diameter, frame-rail tubes as scrap. The sections were a bit short though, only 90 inches long, rather than the 93 inches Negstad had specified on Ford’s computer. Instead of getting new frame rails, though, AC’s engineer concocted an elaborate box structure to contain the rear suspension, which really irked Negstad (as he expressed to me personally in interview at Carroll Shelby’s office). But he finally got his way with the new Superformance Coupe chassis, which is extended 3 inches. He also used the 427’s upgraded coilover configuration, rather than the 289’s transverse leaf setup.

That frame extension proved to have some design advantages for Brock as well, as he feels it allowed him to improve the look and aerodynamics of the body. Before doing so, however, he had yet another controversy to address — the wheel size. Since Jimmy wanted to build a duplicate, more or less, of the original Coupe, the wheels would thus only be 15 inches in diameter.

Brock objected, as no street tire in that size could handle speeds as high as 200-plus mph. He approached several manufacturers about creating a speed-rated tire in that size, but they all declined. So after going back and forth on the matter, Brock and Jimmy finally agreed on 18-inch rims, which could run speed-rated rubber. That also allowed for bigger brakes, and Brock felt they looked better anyway. His revised Coupe rolls on Michelin Pilot Sports (295/35ZR18 in the rear and 245/40ZR18 in front) with his own BRE lightweight modular wheels.

Improving on the Daytona’s original aerodynamics involved revisiting many parts of the car’s telltale roof, starting with the scoops at the rear quarters of the car. Brock points out that the original car — CSX2287 in particular as the one he chose to emulate — had flat Plexiglas side windows. “The air around the A-pillar turbulated,” he says, transforming the smooth laminar flow into a turbulent one. “So the quarter window scoops didn’t work: They created more drag and noise.”

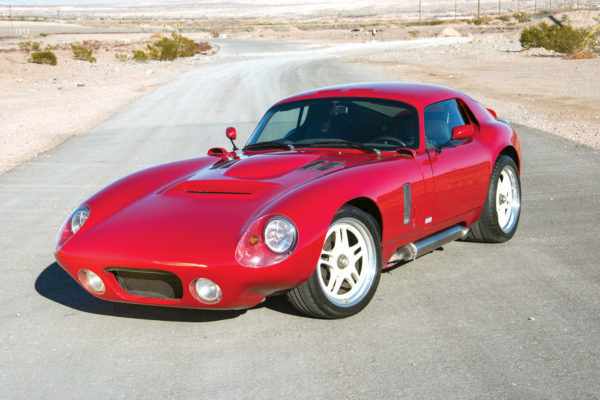

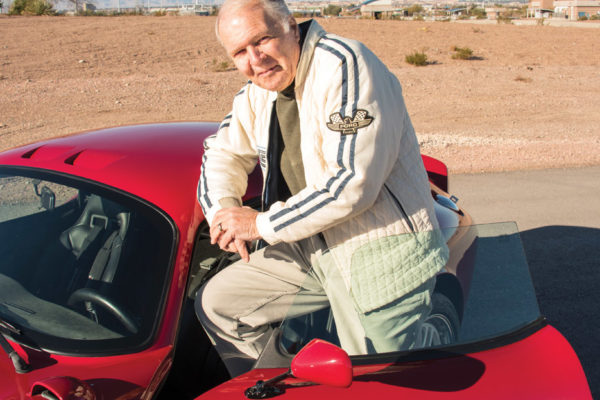

Curved windows solved this air separation issue and also gave the car more graceful lines. The roofline is identical to CSX2287, while later cars built in Italy had a slightly different shape due to the coachbuilders’ mistakes in converting the design measurements from inches to millimeters. But note the two extractor vents that Brock added right behind the top edge of the windshield.

“I wanted to do that on the original cars, in order to reduce heat in the cockpit,” he explains, noting how this aspect can affect driver fatigue. But he had to wait decades, finally adding them to his personal car. (These are not found on the production Superformance cars, by the way.)

The slightly stretched wheelbase enabled Brock to add a bit more radius to the nose, as seen from above, and to elongate the fenders as well. On the other hand, the scoops at the base of the windshield are basically the same as on CSX2287, as are the hood extractor and rear spoiler above the Kammback tail.

As an essential part of the Daytona’s rear end, Brock’s new Coupe features a rear spoiler that’s close to the original design. The spoiler is another interesting detail in the early development of the Coupe, though. Initially the car didn’t have one, and he admits he didn’t know back then just how tall it needed to be. But Phil Remington declined to add one anyway since the car was already running faster than the Ferraris. “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” was a typical response from Remington, Brock recalls. When Phil Hill drove the car at the Spa racetrack in Belgium, however, he found it highly unstable, so a small rear spoiler was added to provide some downforce for the rear end.

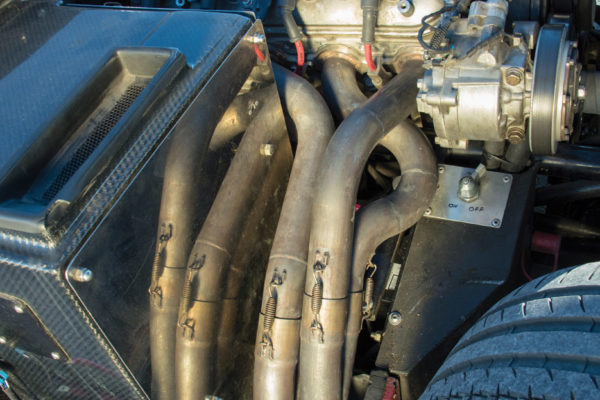

As for the unusual engine setup on Brock’s personal car, it too provided some aerodynamic and handling benefits. The Superformance turnkey-minus package is normally set up for a Ford V8, either small- or big-block, which is what he originally had in the car. For a variety of reasons, Brock later had a change of heart and defied convention by going with a General Motors LS7. The reasons are numerous, but they boil down to advantages of packaging and less cost.

“With the LS crossover induction, there’s lot’s of room above the valve covers. The best thing to do with the extra space is to put it to good use,” he explains. “With an LS, you can raise the crank centerline about 1 3/4 inches!” The main advantage with this setup, Brock points out, is that the flywheel, clutch and bottom of the bell housing no longer hang below the main chassis tubes. With the bottom of the car now clean, the entire chassis can be dropped the 1 3/4 inches, so overall ground clearance is improved and frontal area is reduced. “And it looks way cooler too!” he adds, ever conscious of the car’s aesthetics.

Summing up the importance of this visual aspect, Brock adds, “From an aesthetic/exterior point of view, these Superformance recreations are the only Daytonas with the correct aero-friendly roofline.” He notes in particular the high point over the driver’s head and how the roof gradually slopes downward going forward toward the top of the windscreen.

All told, Brock demonstrates that great designs are all in the details — even decades later. And also that a great designer never rests.

Comments for: Coupe de Grace

comments powered by Disqus