Aluminum Cheetah bodies formed at AAMS

By Marcel Benoit

Photos by Steve Temple, Marcel Benoit and Mark Boen

While most replicas have bodies made of fiberglass, due to its lower cost and ease of fabrication, there’s been a resurgence of late in aluminum bodies. For instance, Mark Gerisch, the founder and president of the Academy for the Art of Metal Shaping (AAMS), has two similar-appearing but very different Cheetahs undergoing construction and/or modification at his facility. Since I’m a Cheetah historian and a former student of AAMS, it made sense for me to cover these projects in detail.

AAMS, as its name implies, is a not-for-profit school of higher learning. Its purpose is to preserve the art of metal shaping, and to this end, offers courses in metal shaping and custom fabrication. They range from a three-day course all the way up to a two-year master-builder course. Gerisch is able to offer these courses due to his nearly 40 years as a coachbuilder and his fully appointed studio, which is complete with a full complement of welding and metal-fabrication equipment. The students of his courses are able to work on some specialty cars such as Cobras, GTOs and the subject of our story, Cheetahs.

Coincidentally, this particular story began when two separate Cheetah owners contacted Gerisch to have alloy bodies constructed for some of their cars. From there, he did some additional fabrication work on a race car and one of the cars featured here. It’s interesting to note that the first two Cheetahs constructed at the Bill Thomas facility in Anaheim, California, in the early 1960s had alloy bodies. A third alloy body for the so-called “Super Cheetah,” or 1965 model, was later constructed from parts of the first car. All the production cars had fiberglass bodies.

Cheetah Evolution

Gerisch’s master-builder students studied TIG welding under master welder Leo Vania while welding the Cheetah Evolution chassis. The whole project was done under the guidance of Craig Ruth, co-owner of Ruth Engineering, sole proprietor of Ruth Restorations, and the mind behind Cheetah Evolution.

While similar in appearance and overall dimensions to the original Bill Thomas Cheetah, the chassis from the aptly named Cheetah Evolution is a leap forward in development from the original Cheetah. Ruth started development of Cheetah Evolution in 2005, and completed his first car in March 2008. He found a rough GTR body from Fiberglass Trends, and sliced and diced it to build his own body mold plug, adding flared fenders to the front of the car in the process. The resulting molded body is something that preserves the original lines of a Cheetah, but manages to be even more aggressively styled than the original.

Since one of Ruth’s current customers desired an alloy body, one of his fiberglass bodies is being used as a buck by Gerisch to create the alloy unit. Underneath the body, Ruth created a new frame design using C4 Corvette suspension components. The Cheetah Evolution frame is built with 1.5-inch, .120-wall round and square tubing (as compared to 1.25- and 1-inch-diameter tubing on the original), along with welded-in 14-gauge floorpans, transmission tunnel, firewall, side panels and rear bulkhead.

While designing his frame, Ruth was also mindful of the cockpit size limitations of the original car. When compared to an original Cheetah, Ruth’s Evolution frame is a full foot longer in the driver/passenger compartment (58 inches, as compared to 46 inches), and more than 6 inches wider across the cockpit area. The resulting frame is able to accommodate a driver up to 6 feet 4 inches tall, and is said to be much stiffer than the original.

True to its name, Ruth’s design has continued to evolve over time. The newest cars have migrated away from using the C4 rear end to a more robust Winters IRS unit, which costs about the same and is also readily available. A fully rebuilt Dana 36 or 44 unit is good for about 800 hp, while the 4.10 Winters unit is stronger (good for a reported 1,000 hp or more).

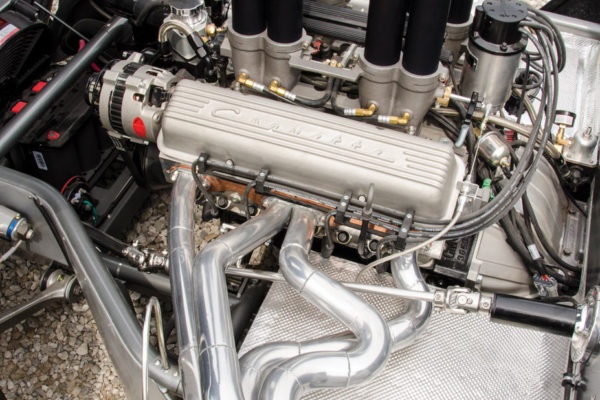

As far as the rest of the drivetrain is concerned, Ruth has installed an equal number of Chevy small-block, big-block and LS engines, but he is willing to work with the customer to fit anything they want. Most customers prefer to link their motor to the robust T-56 six-speed units. The latest iteration of this transmission, the T-56 Magnum by Rockland Gear, can handle 1,000 hp and 700 lb-ft of torque.

While Ruth prefers to build complete, titled cars at his shop in Ohio, he does offer “roller” packages that require a significant amount of work to complete. For ease of registration, Ruth offers a safety glass windshield (the original Cheetahs had 3/16-inch-thick Plexiglas windshields).

Original-spec Cheetah

The other Cheetah in residence at AAMS is owned by Ron Keck of Oswego, Illinois, and is one of the Bill Thomas Cheetah continuation roadsters built by Robert Auxier of Glendale, Arizona. The car is a near-perfect visual match for the original Cro-Sal Cheetah campaigned successfully by Ralph Sayler of Hammond, Indiana, for the ’64 and ’65 race seasons. Keck’s car is competitively driven by Brian Garcia of St. Charles, Illinois, for Keck Vintage Racing.

The 1960s vintage chassis and body design could be improved in a number of areas, including chassis rigidity, suspension geometry and engine cooling. This characterization is not meant as open criticism of the original Bill Thomas/Don Edmunds design, which at the time possessed some novel design features and great lines. After all, Edmunds would be the first to admit the limitations of the design and he has personally expressed surprise at people’s interest in the Cheetah, given its number of shortcomings.

In a 2006 interview, Edmunds admitted that, “The Cheetah, I have to say, in its original configuration was pretty much an awful car … the exhaust system ran across your legs. It was like being in a cement mixer when you drove the thing, it was so loud with the engine noise and general shakes, rattles and rolls.”

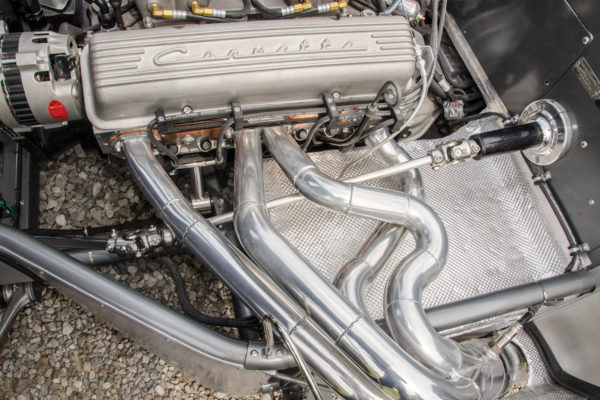

Despite Don’s scathing critique of his own design, he and the rest of Thomas’ crew assembled a rocket ship fitted with a Chevrolet 327, boring and stroking the engine to 377 cubes and adding a dual Rochester fuel-injection unit. Rather than having a driveshaft, the transmission yoke was mated directly to the pinion flange on the then-new, independent C2 Corvette rear end. This assembly moved the engine aft in the frame and gave a 47/53 percent rear weight bias, nearly equal to that of a mid-mounted engine.

So why all the problems with the frame? When Edmunds began building the first Cheetah, he thought he was building a cruiser/styling exercise to show the GM leadership what Thomas’ shop could do, with the hope of gaining follow-up work. Edmunds specifically noted that he did not initially know he was building a race car. He thought he was basically building something to hold the drivetrain and driver in formation under a stylish body.

When he found out the car was going to be raced, though, he exclaimed, “Oh s—,” because he knew the frame he was building was going to be somewhat flexible. By today’s standards, torsional stiffness was lacking due to little triangulation, small frame tubes and no rigidly affixed bulkheads.

Highly skilled drivers like Ralph Salyer and Jerry Titus (and likewise with Brian Garcia) could tame the ferocious feline enough so that it could run competitively, but most mere mortals would be very challenged to drive an original-style Cheetah at speed on the optimum track line. Many have tried, but even very capable drivers have managed to put the Cheetah into ditches, walls and even over guardrails.

Even so, as a testament to Don’s design and fabrication skills, the frames did hold up under the abuse, and no driver was ever hurt driving one. Despite the limitations of the frame and no factory support, the Cheetah was blindingly fast, and enjoyed a number of high-profile victories.

To stiffen up this Cheetah, Gerisch added additional bracing throughout the frame, while preserving its historical qualities. While the car is apart, AAMS will also be installing some much-needed safety improvements to protect Garcia, including kidney plates to protect the driver’s back from broken half-shafts, and side-impact protection.

Furthermore, AAMS will install some added accessibility improvements allowing for improved egress. Garcia is also redesigning the suspension geometry to take advantage of the stiffer frame structure. In addition, Gerisch redesigned the front of the car to include a proper air dam with improved flow to the oil cooler. Lastly, extensive hood venting reduces under-bonnet heat, which plagued the original Cheetah.

Cheetah fans will find developments ongoing at AAMS for both the old and new-style Cheetahs exciting. AAMS offers courses for the beginner to the expert levels, with tailored instruction for specific skill sets. All told, it’s an ideal opportunity to develop your mettle in metal.

Comments for: Ferocious Felines

comments powered by Disqus