Installing a BMW V10 in a Superlite SL-C

As told by Daniel Gherhsin

Photos by Steve Temple

John F. Kennedy delivered a pretty famous speech back in the 1960s about choosing to go to the moon. He said that we would do such things, “... not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

Maybe that should be the motto of my Superlite SL-C build because it sure wasn’t easy. The most difficult part was integrating the highly sophisticated F1-inspired, BMW V10 engine in a chassis that was primarily designed for a compact V8.

I’ve always been intrigued by high-horsepower, inline-six engines. So before building the V10 Superlite, I built a high horsepower 1995 Toyota Supra Turbo. It was my dream car as a kid, and I remember wanting to know how it would feel to drive a really high horsepower car. I knew if I put my brain to work, anything was possible.

So I built myself a 1,400 hp Supra with all the bells and whistles, including the famous 2JZ-GTE engine, mine being a 3.4-liter stoker with forged internals, a 91 mm turbo and a MoTeC ECU. With that output in mind, I also included a Tilton triple disc clutch and upgraded everything in the rear end to hold the power. It was a beast of a car. It would get traction at about 100 mph and go from 100 to 200 mph, literally, in seconds. It was so scary to drive at full potential. Let just say I had a lot of respect for that car because of its ability, but it was also the main reason I didn’t want to keep it. It was great while it lasted, but horsepower is expensive and so was the rebuild every season. I decided it was too much for me, so I decided to part with it.

When I sold my Toyota Supra, I knew I was going to start a new project. Except this time it had to be better, more unique, not quite as fast and something with an exotic look. Once I saw the SL-C online, it’s safe to say I was hooked. I later found out that the Superlites were built literally one hour away. That following Monday, I called Fran Hall and he was eager to show me around this shop. We discussed many things including the most important one — engine plans. I initially wanted to put the same 2JZ 3.4-liter stroker engine that I was familiar with, but I knew I wanted a more exotic exhaust note. That’s where I came up with the odd-fire V10 option from BMW, the S85B50. Fran always supported my idea and thought it would be a great match.

Prior to lowering this impromptu power plant into the chassis, hundreds of hours were spent carefully planning and designing every component that was to be installed or modified. Many gearheads I know combined their experience and knowledge with mine (as a BMW master tech by trade) to help this vision become a reality.

Before the chassis was fabricated, I purchased the BMW engine from another car enthusiast who was parting a car out after being T-boned. He was very meticulous about how everything was disassembled, which is why I went that route. His M5 was a super low mileage, pristine car that was driven around town on the weekends. A crate motor from BMW is roughly $25,000 without any accessories, so it would have run me north of $35,000 for a brand-new S85 with all components and accessories.

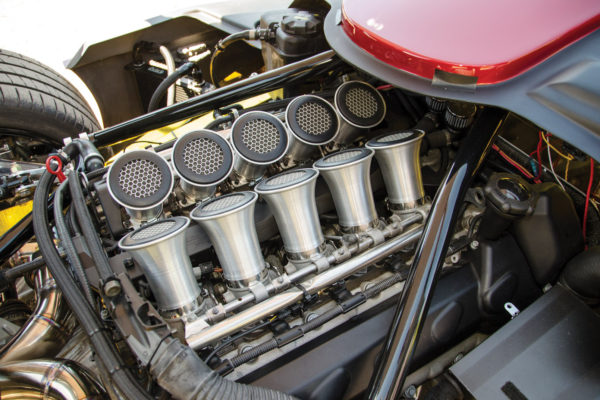

I dropped the engine off at Superlite Cars & Race Car Replicas (RCR) to have them take measurements and determine fitment. The chassis had to be redesigned around the bulkhead, thanks to the additional two cylinders. Based off the measurements I took, it was possible, but a lot of work needed to be done.

In addition to bulkhead modifications, the fuel tank, custom engine mounts and roll bar all had to be redesigned to accept the larger cylinder heads. Matching the engine to the transaxle was all completed by RCR. This included making a custom adapter plate from the S85 to the Graziano transaxle. That required a custom flywheel and crank sensor pickup.

BMW designed the crank sensor to be installed on the transmission bell housing with the reluctor pickup wheel attached to the flywheel. Using that system wasn’t an option for me with my unique transaxle setup, so Fran and his team designed a new flywheel with a custom reluctor wheel. The crank sensor is no longer mounted on the transmission, but in the valley of the engine where the original starter used to be. That required taking precise measurements to eliminate synchronization issues with the cam sensors when we first fired the engine.

I had a number of sleepless nights trying to figure out how I was going to make this or that work. Many times I told myself it can’t be done, trying to discourage myself from installing the 575 hp V10 engine in my SL-C. But something inside me kept pushing. Maybe it’s because I built my very first car at the age of 16 and haven’t stopped since!

This leads me to the complexity of this engine and how advanced the ECU is. It uses a multilayer circuit board with over 1,000 individual parts. There are three 32-bit processors, which allow a combined capability of over 200 million engine calculations per second. The ECM is also responsible for monitoring over 50 input signals.

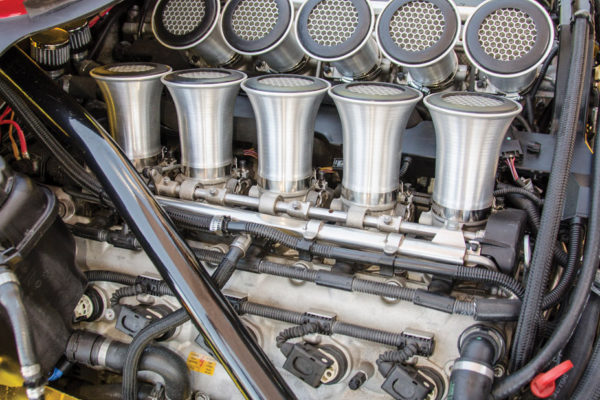

The S85 has 10 individual throttle bodies with two CANbus controlled throttle actuators. I remember dreaming once about how I was going to get the GM accelerator pedal to work with the BMW throttle actuators. The next morning, I woke up, turned on my laptop, and started calibrating different values for the accelerator pedal.

Programming new values into the ECU to correct for the different millivolt values was challenging, but it was possible after hours and hours of testing, failing and trying again, until it would no longer set into fail-safe mode. By the end of the day, I had accomplished something unreal. I had a GM accelerator pedal controlling a BMW V10 engine!

Another challenging aspect was the S85 engine oiling system. It’s a quasi-dry sump; therefore, multiple oil pumps are used. This engine has a total of five oil pumps, including one main 5-bar pump, a suction pump that transfers oil from the front section of the sump to the rear, two lateral oil pumps that are activated in excess of 0.8 Gs and one VANOS (BMW’s variable valve timing system) high-pressure oil pump that runs the VANOS actuators. The oil sump system was modified to allow for a dipstick, since the BMW system utilizes an electronic measuring provision through the iDrive system.

I improvised and modified one from a BMW M62 engine. After removing the sump, I drilled and added my own custom bung to the top of the sump. Once welded to the sump, I then used water to measure the full mark on the dipstick. It was a lengthy process but definitely had to be done.

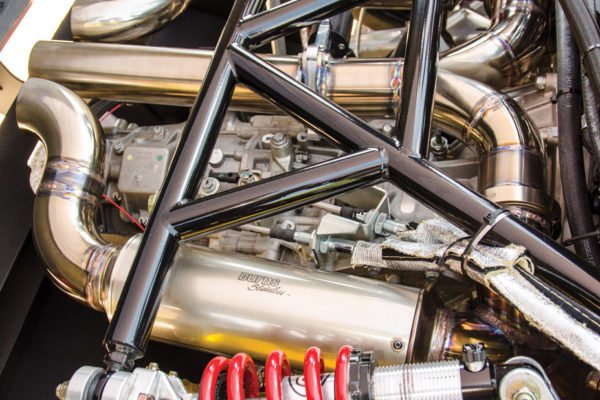

Now to my favorite part of the build: designing an exhaust system that delivered the best possible sound from this S85. Being that I live in a quiet neighborhood, I wanted to achieve the quietest possible exhaust with the option of having an electronic switch to let the beast roar when I needed it to.

I decided to keep the original equal-length headers but modify them to clear the transaxle mounts. Also I wanted to incorporate quality stainless mufflers that could be serviced. I contacted Burns Stainless, and the firm took interest in my little project. The company made custom mufflers with 2.5-inch cores and 3-inch outlet mufflers that would be repackable just by removing the body. I also installed an electronic control valve to actuate the exhaust note to my liking from the flick of a switch. The exhaust note in the higher rpms is unbelievable!

In the cockpit, the AiM MXL2 dash system can be programmed to display anything the ECU sees. It acts as a data logger as well, and it can be used on race tracks with a preset track layout (GPS-based) to record data going around the track. It also has a rearview camera that’s on at all times, and the display is on the top where the rearview mirror would normally be installed.

To me the whole project was mind-blowing because I knew firsthand from my job just how difficult it is to integrate non-OEM parts with BMW components. This two-year build consisted of many different challenges to overcome. Thankfully, I have a very supportive wife and a great group of guys in my life who made all of this possible. I would like to thank them and everyone involved because I know it would have been an impossible task to take on alone.

Like JFK’s inspiring moon-landing speech, this project of mine had a mission in mind: “… that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win …”

Now that I’ve completed this mission, I just have to figure out what my next “moonshot” will be.

Comments for: Moon Shot

comments powered by Disqus