An aluminum Triumph-based Italian roadster

Story and Photos by Iain Ayre

The look is Italian, but it might surprise you to learn the shape was formed in the U.K. This coachbuilt, aluminum-bodied spyder bears an evocative badge, akin to the howling little featherweight sports racers from Milan in the early days. Tiny engines, multiple camshafts, numerous barking downdraft Webers, and popgun tailpipes leaving trails of dust along the sepia-toned route of the Mille Miglia race — these are characteristics of a group of cars known as Etceterinis. While the nomenclature is specific to small Italian racers of the ’50s, this custom aluminum-bodied spyder masterfully executes the Etceterini formula, on a proven English donor.

The badge on the hood says “Giata Bandini,” and claims an origin in Milan and echoes of independent Italian postwar craftsmanship are evident in its finished shape. But a closer look starts to reveal some international elements.

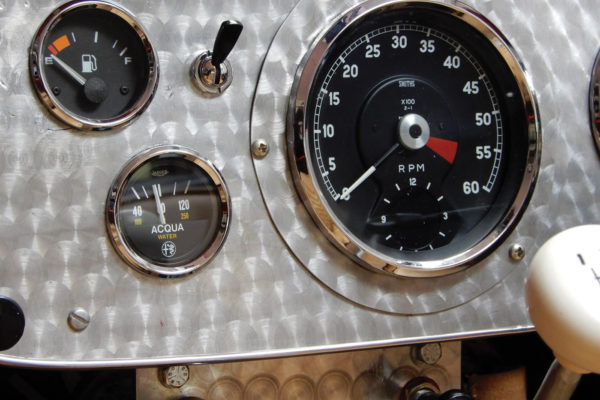

Inside the cockpit, you’ll find a Smiths tachometer out of an old Jaguar and a speedometer from a Triumph. While the temperature gauge is from an Alfa Romeo, the OLIO gauge is a dual oil/water gauge out of an MGB. Moreover, the Superleggera tubing in the cockpit can be traced forward to a Triumph Spitfire firewall and dash structure, covered up by a hand-turned aluminum dashboard.

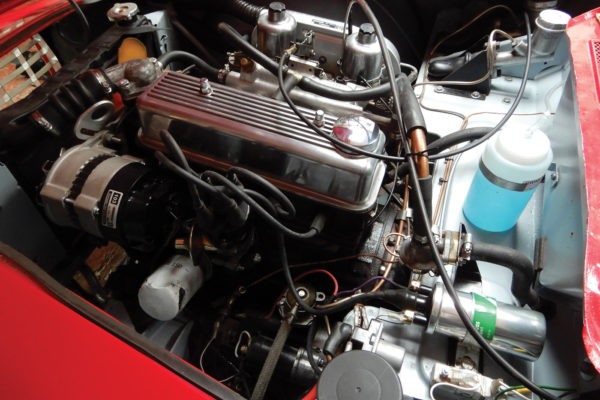

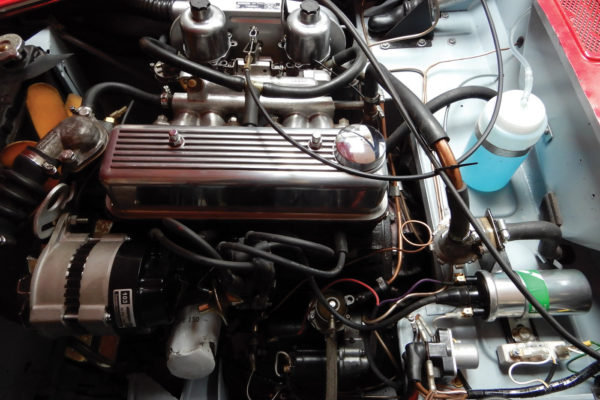

So don’t be surprised upon opening the hood that the first badge you’ll find is British Leyland, not Motore Ermini. The engine’s origin is obscured for most people by the alloy rocker cover, but with the hood up, anyone familiar with Triumphs would instantly recognize the Spitfire engine and the stock Triumph firewall. The spiritual origins of John Selway’s “Spitfirrari” (or Triumphini, if you will) may indeed be in Milano, but it was actually crafted in the English Midlands.

John’s attraction to engineering and lightweight metal creativity was probably sparked by his father, a pilot who used to fly him from Ireland to school on the south coast of England in the family’s Percival Proctor. What a magnificent way to be taken to school, indelibly imprinted on John’s young mind.

In 1961 John became an apprentice at Vauxhall Motors, owned by General Motors since 1925, but left after a decade or so, having learned all that he was going to. In 1974, he became an independent car engineer and constructor and has been honing a variety of skills ever since, specializing in aluminum bodywork. Today, he could make you a Spitfirrari, but there are thousands of costly hours in the project.

The flip-front design of the smaller Triumphs is very useful for rebody projects, as removing it leaves the rest of the car complete and drivable. There’s no need for any structural changes at the front, as the new bodywork essentially drops right on the Triumph rolling chassis. The new inner wheel arches form part of the new fixed fenders, and the body tubing was simply connected to the chassis and bulkhead. The Spit body is about the right height, and this donor car provides pedals, seats, rails a fuel system, heater and a suitable basic structure, so there was no point in duplicating all those efforts.

The frame, running gear and some basic body substructures remain from the Spitfire, but all the external bodywork has been recreated in the Superleggera style. It starts with a framework of light steel tubing, which is then sheeted with hand-formed aluminum panels. The sheeting is constructed by hand with old-school hammers, dollies and an English wheel. John also crafted the inner wheel arches and the floors from aluminum.

The doors are completely new, with fabricated simple steel hinges hung from new steel tubing around the door edges. The hinges are lightweight affairs, because they don’t have to support the relatively massive pressed-steel Triumph doors, with their heavy glass, winding mechanism, exterior and interior handles, locks, and other arrangements. Only the weight of plastic side curtains needs to be accounted for, and these are rarely fitted. There are no external handles on the new doors, just MG TC interior chrome catches and levers. Since their external skins are a single sheet of aluminum, the doors likely only weigh 10 pounds per side.

Fabricating these lightweight doors is a little easier than it sounds, as they’re very nearly a single curve. The tube frame is bent to make the shape of the door, then the hinges and catches are welded on. Finally, the oversize door skin is attached by having its edge delicately hammered around the tubing.

The trunk lid and hood are made in the same way and are also relatively weightless. Every single panel on the car is a collection of aluminum pieces wheeled and welded together with old-school style, talent, oxygen and acetylene.

The cheekiest part of the whole car is the windshield, which believe it or not is also Spitfire, although it looks completely correct and convincing. The screen is stock Spitfire safety glass, but the original windshield frame has been replaced with a delicate, one-off surround in chrome-plated brass.

John’s dashboard is a simple flat slab in an Etceterini style, with an engine-turned aluminum surface. The instrument placements are slightly random, with pride of place given to the tachometer, which is period- and location-correct for a small Italian racer.

The seats, handbrake, gear lever, and its shroud remain pure Triumph, and the interior really could be further Italianated. It’s actually quite easy to make authentic-style bucket seats and leather shrouds for the gear lever and handbrake, but on the other hand, leaving some telltale Triumph clues just adds to the fun.

You could spend years on such a project, and that’s exactly what John did, pottering on with it during the quiet times. The car isn’t exact copy, but instead is an elaborate pastiche, designed to puzzle and then amuse and titillate even the experts. But it’s also a beautiful, entertaining, and practical sports car, much lighter and faster than the Spitfire donor.

For more information on John Selway, contact us at editor@rcnmag.com.

Comments for: The Spitfirrari

comments powered by Disqus