Stopping Spree

Story and Photos By Dan Burrill

In the old days, car builders worked first on getting their rides to run fast, and then worried later about stopping. Today, though, high performance includes good braking as much as a hot engine. After all, when you keep up your speed longer going into a turn, you can dive deeper into the curve than your competition. What follows is an overview of various brake systems for both the street and track, along with a few tips on making the right choices.

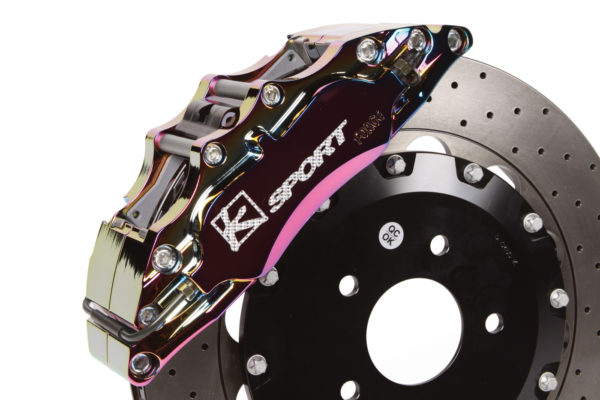

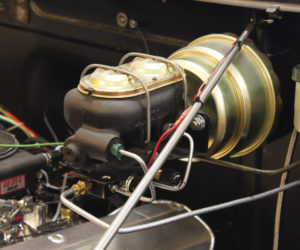

When we talk about the brakes, we are really talking about the three main parts that make up the brakes: the caliper, rotor and pads. Whether or not you invest in expensive rotors, fixed calipers, or any other high-tech brake parts, two of the parts are going to be expendable: pads and rotors.

Depending on use, pad life is usually around 30,000 to 50,000 miles. The rear pads will last longer because 75 percent of your braking is done with the front wheels. And, of course, if you are racing your car on the weekends, the pads will wear even faster.

On the surface, all brake pads look more or less alike, even though there are wide variations in design and materials that affect how well your vehicle stops. You need to choose a pad that offers you the best braking for the kind of driving you’re doing. The key here is the operating temperature of the rotor.

Racing pads are designed to offer their best grip when the pad and rotor are very hot — as they would be on a race car in the heat of competition. However, they may offer substantially less grip when your brakes are cold.

In most street driving, your brakes may never get hot enough to get the benefit of those pads. Plus, they’re expensive and may eat through your rotors faster than a pad designed for street use.

By the same token, you don’t want to take your car to the track for a long day of performance driving with basic street pads on the front end. The reason being is that brake temperatures can shoot past 1,000 degrees F, and few standard brake pads will tolerate that. Changes in pad technology have contributed to higher temps.

“Back in the 1960s, we used to drill holes in rotors to obtain a kind of cheese grater effect, because the coefficient of friction of brake pads was low; about 0.3. Now we have pads with a coefficient of friction up to about 0.6, which dumps a lot more heat into the rotor,” says Warren Gilliland, the brake engineer behind The Brake Man (TBM). “If you can get your head in there, you can look at your brake pads through the caliper and see how much pad you have left.”

Your first order of business is to buy the best front pads you can find. The main types of brake pad on the market today are ceramic, semi-metallic, and pads made with advanced materials like Kevlar or Aramid fibers.

“If your only concern is how your car looks, and you want to avoid dusting up your wheels, you need a ceramic-based pad,” notes Michael Hamrick of Wilwood Engineering. “If you’re going to take the car to a track or run autocross, you need semi-metallic. If you’re going to go out and run the car longer than a 15- to 20-minute session on a racetrack, you need a full-out racing pad. You haven’t got a choice.”

So how do you know what you are buying? A good place to start is to check the numbers or letters on the pad or on the box. Developed by the SAE, a typical edge code starts with a three-letter identification, then an alphanumeric code that references the type of friction material, two letters that specify the friction properties, and then a numeric date that specifies when the pad material was produced.

The part of the edge code you care about most is the friction properties code. Friction is specified as E, F, G or H. As you might expect, E is the lowest friction rating, while H is the highest.

The first letter in the code is the pad material’s cold friction — think about the first time you apply your brakes in the morning. The second letter is the hot friction rating — when the brakes are fully up to temperature. In general, high-performance pads will have G or H ratings, while street pads will have E or F ratings. The only real drawback to these codes is that they don’t cover heat ranges, wear or dusting characteristics, but it is still a good basic guide.

Here’s something to keep in mind before installing new pads: “If you buy new pads, don’t put them over the top of the friction material that has already been transferred to the rotor,” Gilliland points out. “It’s very important to remove that. If the rotor’s in a good flat condition, a vibrating palm sander with 80-grit sandpaper will remove the material transferred from the stock pad.”

He adds that if you don’t remove that layer, you can significantly impair the new pad from laying down the material to properly give the performance you should have. Most people think they have warped a rotor when they just have material built up unevenly on the rotor.

So let’s stop here!

Comments for: Stopping Spree

comments powered by Disqus