Competition Power

By Steve Temple

Photos courtesy of Craft Performance

It’s a given that every replica needs a good engine. Without a solid motor under the hood, you’ve basically got a sheep in wolf’s clothing. But what if your replica is heading for the track — either a road course or a drag strip? Things get a bit more complicated, since an off-the-shelf crate engine typically isn’t tailored for track duty.

To get some practical advice on what makes for a racing mill, we sought out Lance Smith of Craft Performance Engines. This company has been making high-performance engines since 1992. With a reputation for winning, Craft engines have been used to set over 50 national NHRA records.

“The majority of our engines are not crate engines,” Smith points out. “Our crate engines are more of a starting point. We’re real flexible.” Typically, a competition engine build takes a couple months to complete, and includes a camshaft customized for the intended usage. In addition, other variables factored into the build include the weight of the car and the transmission’s final-drive ratio, along with the differential’s gear ratio.

We decided to focus on a couple of Craft’s stroked small-block V8s in particular, one destined for a Cobra roadster from Factory Five Racing that’s being set up for road racing — along with a bit of street cruising. (Maybe to bait some unsuspecting Corvettes?)

The other is more of a “triple threat”— suitable for street, road racing and the drag strip. Although it’s being dropped into Smith’s personal 2006 Mustang, it could fit in a Cobra as well with custom headers and a taller hood for clearance. We’ll focus on the specs of each engine in order to reveal how they differ for individual applications, and also some special tweaks unique to Craft Performance that can significantly improve performance.

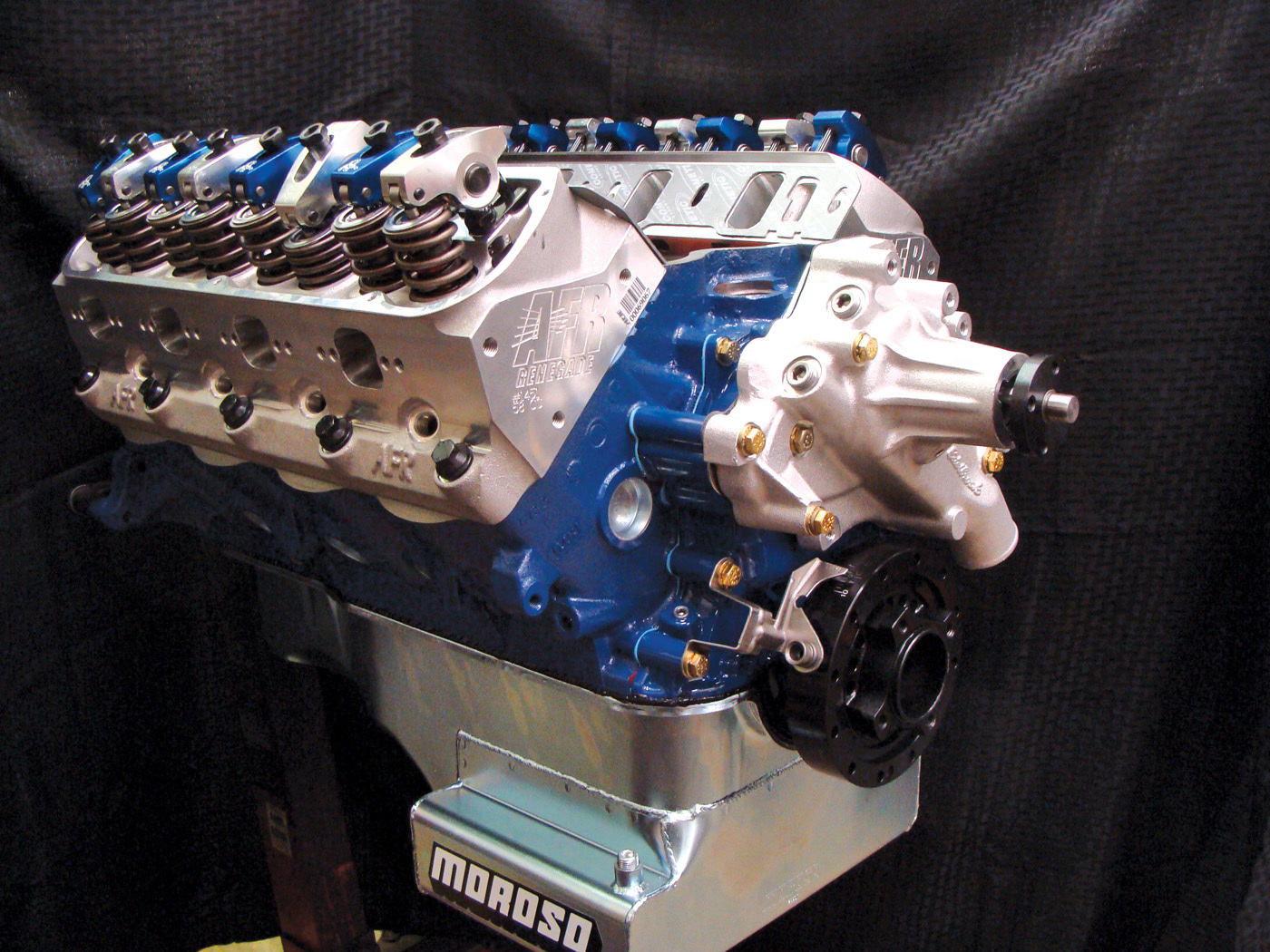

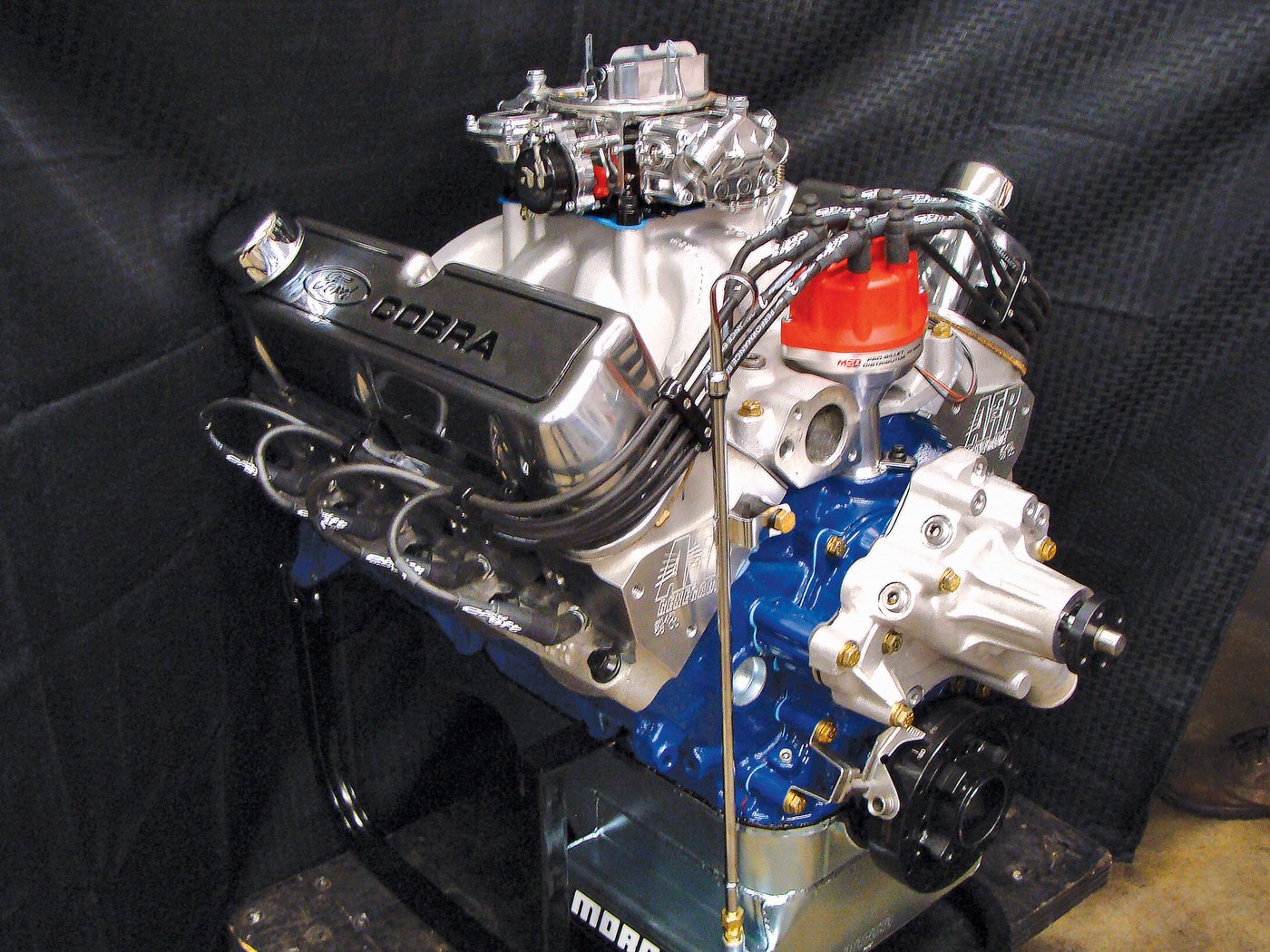

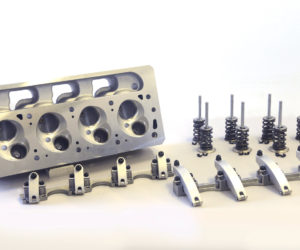

These AFR heads are ported in-house at Craft Performance, and have one-piece stainless steel, 8 mm stems to reduce weight. The retainers are lighter in weight as well, and are made of steel instead of titanium for more durability.

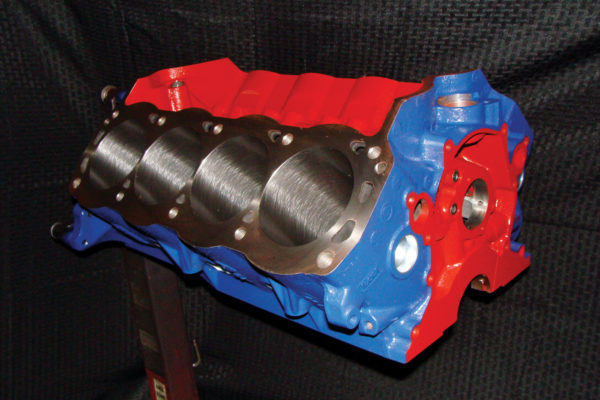

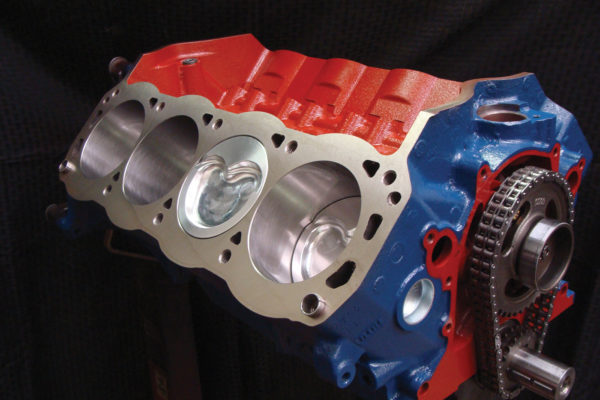

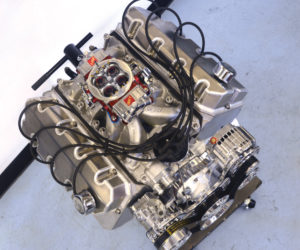

Starting with the Cobra’s engine, it’s a Dart 351 Windsor block stroked to 461 cubes. Typically a 351 has a 4-inch bore, but that’s been punched out to 4.155 inches. The standard stroke is 3.5 inches, but it’s now elongated to 4.25 inches using a Scat crankshaft, notched to give clearance for the H-beam rods (measuring 6.125 inches). “Stroke is where you get your torque from,” he says, which is what you need on a road course.

The Diamond Dish pistons have a 10:1 compression ratio, (the same pistons used for a 3.25-inch stroke, 4.155-inch bore, low-compression 302 engine), so the engine can run on pump gas. That’s because, “A bigger bore detonates more easily,” Smith explains.

Topping off the engine are AFR 220 cc heads, CNC-ported by Craft, with a Comp Cams hydraulic roller camshaft with a lobe separation of 110 degrees. “A separation of 106 or 107 degrees is more spikey,” Smith notes, which is less desirable on a road course.

The port-matched Edelbrock Victor Jr. intake is topped with a 780 cfm Quick Fuel carburetor. Smith feels this size of carb works really well for road racing where the revs don’t exceed 6,500, while an 850 or even a 950 cfm would be better for even higher revs seen on a quarter-mile sprint. The heads can’t be too big either, but “an Edelbrock Super Victor would to achieve killer power on the strip,” he adds.

This 461 road-course engine is no slouch, though, delivering 645 horses and 655 ft-lbs of torque. More important for the application is an extremely flat torque curve, with the dyno indicating 600 ft-lbs from 3,000 to 5,700 rpm. “That’s ideal for coming off the corner,” Smith notes. He says the owner of the Cobra wants to keep the TKO 900 trans in third gear as much as possible, and it runs a 3.55 rear end ratio.

As for the engine going into Smith’s Mustang, it also started life as a Dart 351 Windsor short-deck (9.2-inch) block, but is now a 380 ci Windsor, and fitted with Cleveland-style Brodix heads. The bore is the same as the Cobra engine, 4.155 inches, but the stroke is 3.5 inches, using a Callies 4340 steel crank and 6.2-inch rods swinging Diamond Flat Top pistons (resulting in a slightly higher 10.5:1 compression ratio). The differential has a lower 4.86 ratio than the Cobra’s, and the engine peaks higher, at 8,500 rpm.

Recalling Craft’s flexibility noted above, Smith points out, “This engine could also be done as a 3.75-inch stroke (407 ci) in the 9.2-inch block, or in a 9.5-inch block with a 4-inch stroke (427/434 ci), a 4.17-inch stroke (446/452 ci), or 4.25-inch stroke (454/461 ci).”

The Quick Fuel carb has a slightly lower flow at 750 cfm, but that’s through Craft’s CNC Dimple Ported Brodix BF300 cylinder heads. These dimples (also called “snakeskin” by Craft’s customers) are on the intake runners, look a bit like the surface of a golf ball, and are designed to improve the atomization of the fuel. “It has a tumbling effect, while fuel on a flat surface puddles up,” Smith explains. In other words, the rougher surface disperses fuel better.

While the flow-bench numbers are about the same, the dyno numbers show an increase of 10 to 15 rwhp, and 20 to 25 ft-lbs of torque, he notes. The result is 680 hp and 550 ft-lbs of torque. While the horsepower numbers sound better in theory, what changes would Smith make if he dropped this “snakeskin” mill into a road-racing Cobra?

Since the Cobra is a lighter car than the Mustang you can typically get by with a little more duration on the camshaft. Even so, these cams will typically run in the 250-260s at 50 degrees of duration for a road race application, and 260-270s on duration for a drag race engine, along with a higher compression ratio.

So all told, achieving competition power is not only about peak levels, but also tuning the torque curve to the track.

This 645 hp, 461 stroker engine is headed for a Factory Five Cobra road-course racer.

Comments for: Competition Power

comments powered by Disqus