Metalworker’s Art

Story and Photos by Iain Ayre

Robert Maynard of RWM & Co. has spent his life repairing or creating shapes in steel and aluminum. Not one to keep things a secret, he gladly showed us the rudiments of how it’s done.

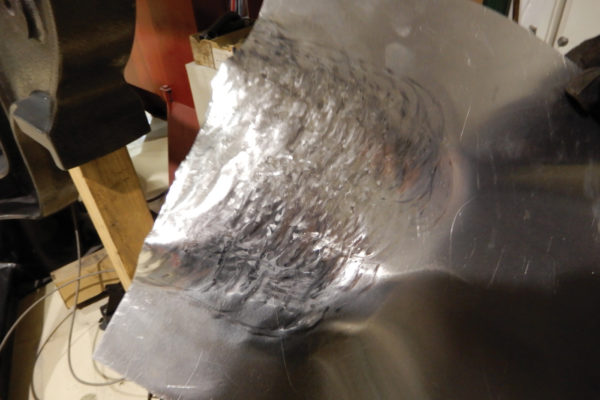

Essentially, you stretch a flat sheet into a compound curve by bashing it with hammers of one sort or another to stretch or shrink it. Next, you roll it back and forth, squashing and smoothing it between the compressed rollers of an English wheel, and then finishing it with a planishing hammer.

Easier said than done, of course, as it takes some years to be able to make things exactly the shape you want.

But given time and patience, a novice could certainly achieve a respectable result making something simple like a hood scoop. Hammers, sandbags and cheap English wheels, good enough for limited hobby use, can be

found at Harbor Freight. Somewhat harder to come by is significant patience, though.

There’s also the tricky business of work hardening. If you work the aluminum too much, it gets very hard and has to be heated and cooled to anneal or soften it. But it also has to be hard when you’ve finished or it will be too delicate for car bodywork.

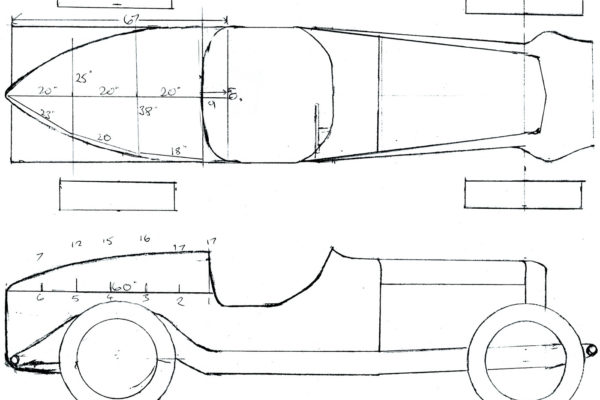

The patience aspect stopped me dead in my tracks. I’m building a Bentley special, built on the rolling chassis of a 1940s MkVI 4 1/2-liter Bentley. It’s to be a two-seater in a 1930s style, with a doorless boattail body in aluminum. The chassis is 40 inches wide, and the tail will be about 50 to 60 inches long. I know roughly what shape it needs to be, so let’s get on with it, right?

“No, no, no, no,” objects Robert. “We have to design the rest of the body first.”

“But we know most of it. The tail looks like a Type 35 Bugatti. I’ve already drawn it.”

“It doesn’t work like that,” Robert points out.

“Scaling up doesn’t really work, for a start.” Okay, I accept that, but I want to get on with it.

“Let’s go and measure it, then,” says Robert. “But it may not even be possible, since 99 percent of Bentley specials are ugly. There are reasons for that.”

He’s certainly right about that. The most likely back end look with amateur compound curves is an obese bumblebee.

The fundamentals of the chassis are wrong: to make a high, upright sedan into a low sports car we’ll have to chop the frame back to the main rails and start again. The engine and box will have to go back 14 inches and down 6 inches. My plan to recycle the original steel hood is dropped, as it won’t match the boat tail. We’ll have to make a new hood as well.

“On that basis,” says Rob, “we can make a beautiful car.”

The two sides of the rear deck panel are fairly straightforward — they’re fairly flat, and long enough for the curves to be quite straightforward to hammer and roll. The tip requires much more dramatic curves, so that is what we are going to show you how to make.

Comments for: Metalworker’s Art

comments powered by Disqus